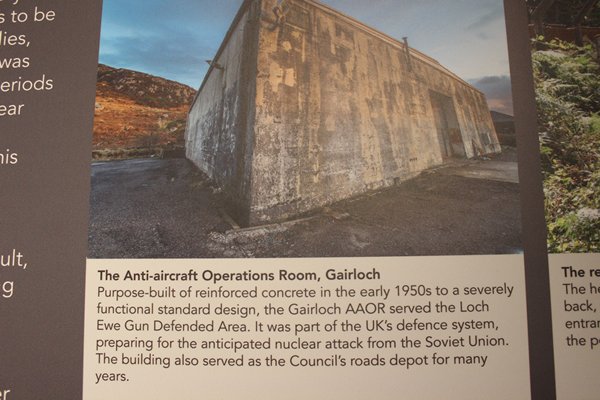

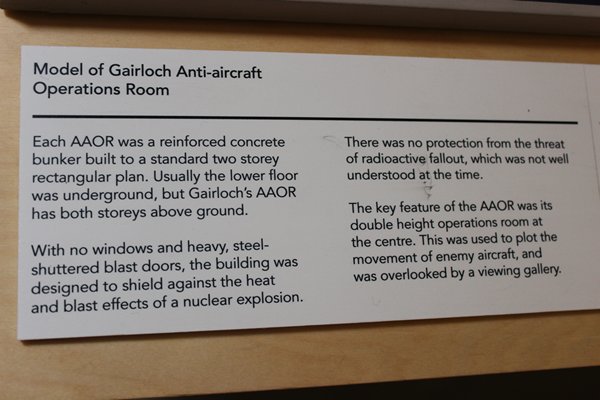

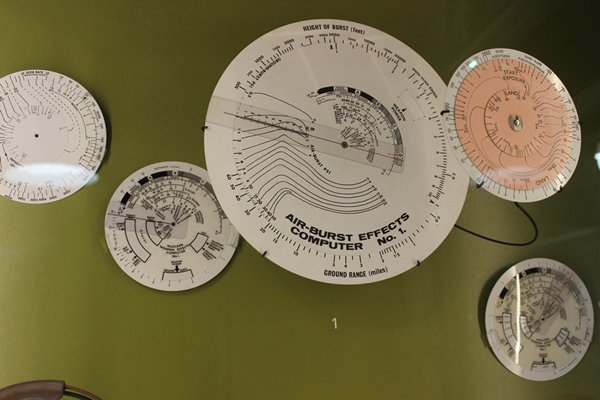

The building itself shows the innovative use of this concrete bunker, built during the Cold War to protect its occupants from the damage of a nuclear blast from Russia, our allies in World War II and, so soon afterwards, our potential enemies. Painted white today the museum is a fine and durable home for the recorded history of the area.

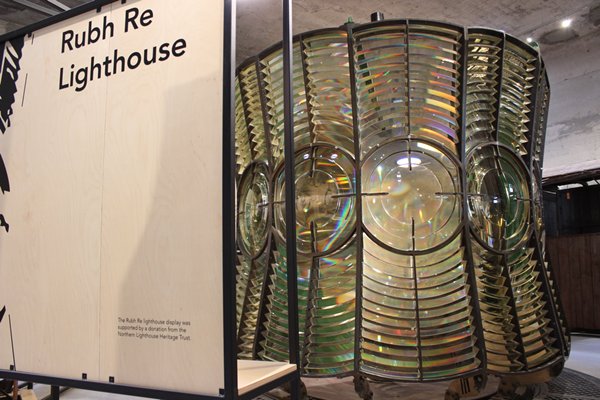

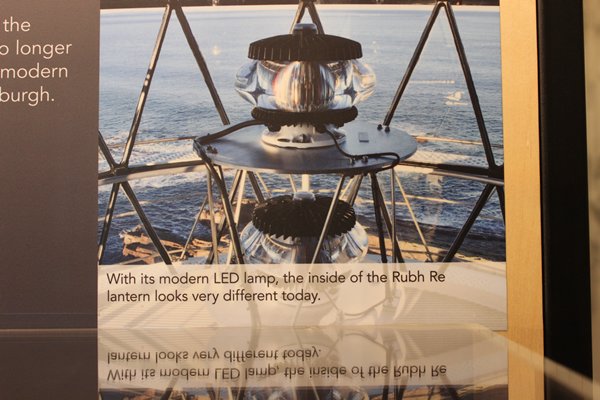

But it’s not all gloom and doom with the dominant feature as you enter the ground floor display area being the entire, old lantern from the nearby Rubh Re Lighthouse, incredibly beautiful in its functionality. To let the lens stop revolving and the lamp extinguish was a sackable offence and the keepers had to work non-stop for 48 hours once, turning the mechanism by hand as the mechanics had failed, before the engineers arrived. Today the LED light is fully automatic and much smaller. Such are the advances in science and technology.

Imagine cleaning every facet of the lens every day!

Rubh Re was automated in 1986, and no doubt the lighthouse keepers had mixed feelings about being no longer needed. The end of a way of life.

The museum time coverage goes back much further than this though; to the formation of the Scottish rock foundation three billion years ago making it some of the oldest rock in the world. The little tectonic raft of rock that is now North West Scotland then spent over one billion years floating all over the earth’s surface, including to the South Pole, before it joined to the four other land masses of Scotland; North Highland, Grampian, Midland Valley and Southern Uplands, and England.

Dinosaurs came and went and the sea level has risen and fallen like our daily tides and long ago the landmass finally broke away from North America, a split causing many volcanoes to erupt and give the west coast its characteristic, if eroded typical magnificence, including Skye. The Caledonian range barged into the east creating what is known as the Moine Thrust, which can clearly be seen locally but stopped at nearby Kinlochewe.

Naturally, due to its high latitude, nearly 58ᵒ N, the area was engulfed by the ongoing ice ages, the chilly artists of the past, which sculped the land into ‘v’-shaped valleys following the contours of faults and rivers; creating the unique beauty for us all to appreciate and feel its direct line to our searching souls.

The cold, treeless, tundra grew mosses, lichens and early plants like crowberry, attracting reindeer and other arctic animals like hare and fox. The effects of gradual warming were the growth of scrub birch, willow and hazel and their rotting leaves created fertile soil which encouraged alder, oak and Scots pine to grow into dense forests. I wonder where the seeds came from? Anyone know?

Then of course there was a migration of woodland animals, northwards into this new habitat; deer, wild boar, otter and beaver and their predators, wolf, lynx and bear.

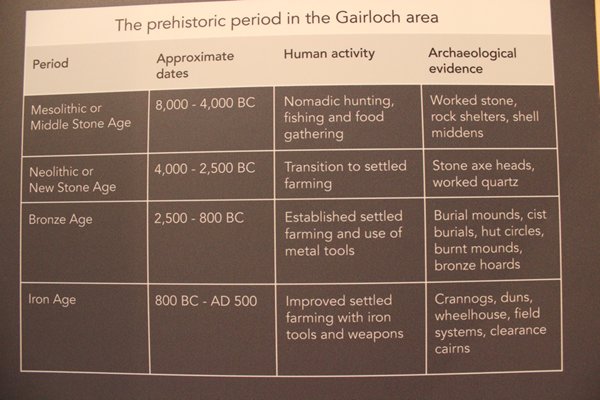

The earliest so far recorded humans arrived on the shores of Rum about 6500BC. They must have thought they’d landed in the perfect place where hunting and fishing rendered farming unnecessary in their nomadic lives. In Gairloch itself, evidence in the form of Mesolithic stone fragments used in toolmaking have been tentatively dated at around 5000 BC.

Over time and possibly because of over hunting or the deteriorating climate, or both, groups of humans started building more permanent homes, roundhouses using locally gleaned materials, lots of glacial rocks for example and driftwood from the beaches for roof beams, covered with a thatch of reeds from riversides.

The semi-permanence of their lifestyle fuelled the will to worship and a 17.5m diameter, roofless stone building has been found in Wester Ross, the entrance aligned on the winter solstice sunset and showing a very hot fire had burned at its centre. The charcoal has been dated to 254 and 213 BC.

Prehistory continued through the different ages you will have heard of; I will let the photo, simply laid out, summarise them for you. Until we get to 500 AD.

Christianity filtered north from Ireland, with the first missionary thought to be Donan, a contemporary of St Columba. Paganism was absorbed by the new faith and occasionally dominated it; for example, in 1678 a Mackenzie family was summoned to Dingwall for “sacrificing a bull in a(n) heathenish manner in the island of Ruffus, commonly called Ellan Moury, in Lochew.”

Then the Vikings arrived in the 9th century, not a single one sporting a horned helmet! Mostly Norwegians, they held sway until 1263 when they were finally sent home after the Battle of Largs on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Their influence lives on of course in the DNA of the present local residents and place names, most especially on the outlying western islands all of which were made Norwegian territory under a treaty in 1098.

‘Clans’ may be a short word but its influence world wide is vast. The aborigines in Australia prefer to be called clans rather than tribes which suggests a tendency to warfare; the North American indigenous people and Maoris of New Zealand are the same, to say nothing of the worldwide diaspora of Scottish clans. It is a global term used by indigenous societies, I discovered repeatedly on our travels. But how different clans worldwide organise themselves varies in many ways.

Over the centuries Scottish clans have shown themselves to be strong and independent, often resisting the influence of the Scottish kings and more powerful clans, fighting for dominance and expanded boundaries.

Gairloch being the home of the Mackenzie clan since around 1494, with the MacLeods constantly vying for power until John Roy Mackenzie succeeded, during his tenure as laird from 1566 to 1628, to bring to an end the murders, battles, massacres and feuds. When he died, he was buried in a chapel in Gairloch Old Churchyard, which is still there.

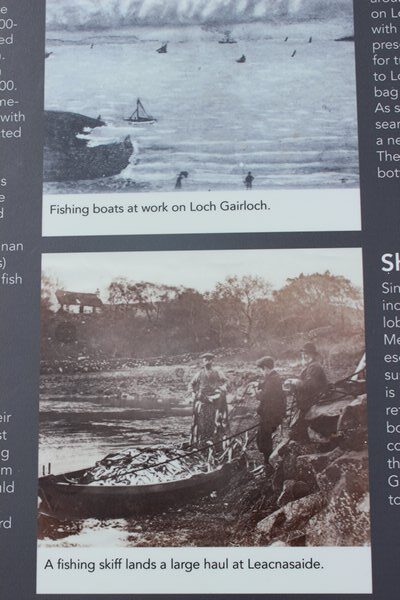

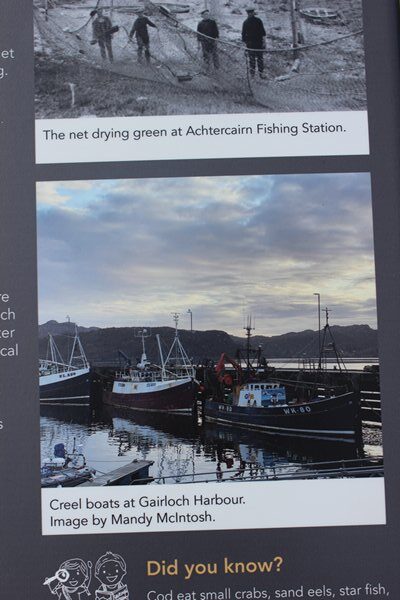

The nineteenth century brought big changes to the Gairloch area under the influence of industrialisation and Sir Hector Mackenzie, laird of the district from 1770 to 1826. Fishing for cod, ling and herring spawned (!) drying and packing stations, boatbuilding of small fishing boats and the bigger sea-going vessels for exporting the produce to Bilbao in Spain. Locals, during a film showing in the museum, spoke of how their ancestors knew at the time that the overfishing of, for example, cod at 40,000 a year, would end in tears and indeed it did. Today fish farms pollute the sea-bed, and just shrimp and shellfish like mussels, crab and lobster are the only locally sourced fish using trawlers and creel lines.

It was the well-meaning Sir Hector who planted the beautiful Flowerdale Arboretum we walked through recently and I put some photos on Facebook.

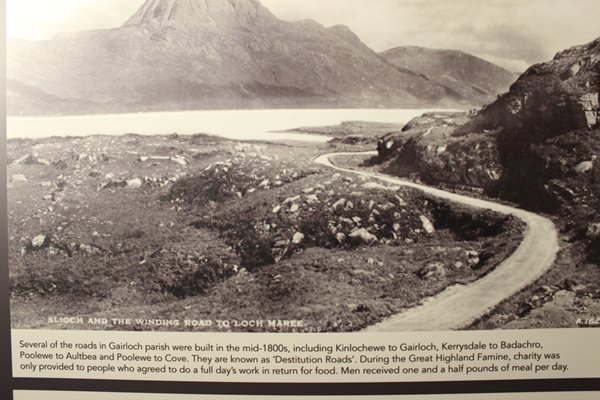

Times were never easy for the crofters. The lairds in Gairloch were benevolent in that they looked after their tenants, but the population was rising and crofts were being divided up into smaller units which barely provided for the large families. Then in 1846 the potato blight hit this vital survival crop. This is when many of the roads were built, called ‘Destitution Roads’, the crofters were paid for their labour in meal, and some voluntary emigration did take place, but nothing like the ruthless clearances elsewhere. It was ten years before the economy started to recover.

Sir Francis Mackenzie’s widow, Lady Mary, set up a home weaving business to enable local women to contribute to their families’ economy, firstly in kind and later in currency. Eventually more than one hundred women were busy spinning wool, which was then knitted into high quality stockings. The female industry deserved their high praise by creating soft and durable socks and stockings in the unique double diamond design, that eventually found a global market.

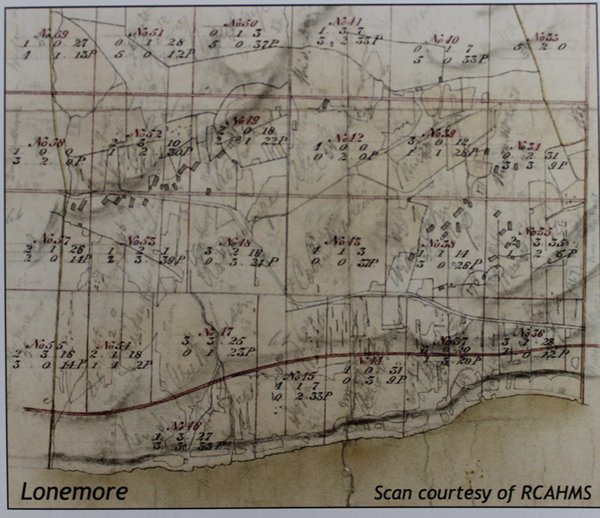

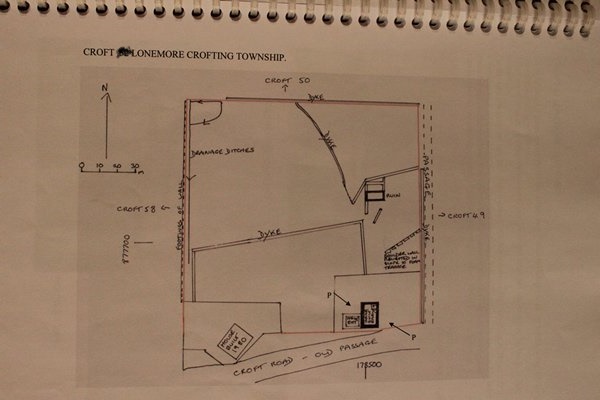

I was taking in the engineering feat of building a croft upstairs and within the concrete walls of this bunker/museum; naturally the walls would be strong enough to support the rocks, but it did seem amazing all the same, when I turned towards a shelved petition where box files stood next to each other, encouraging my enquiring mind to take a peep. Down one of their spines was the name ‘Lonemore’ which I knew to be the name of the lane in which Jane and John’s house was located. A quick flip through and I found the number of their new home on a plastic sleeve containing a few sheets of writing, plans and photos on A4 paper. Wow, bingo. I photographed them to show our hosts and for future reference.

This scan is taken from Campbell Smith’s original survey and the croft number is written in red ink and the designated acreage in black ink. John and Jane’s croft house is in the top left quarter.

In a nutshell, Sir Hector’s son John had trained to be a doctor but took over the running of the estate, after his brother Sir Francis’ death and until his nephew, Kenneth, came of age. At the time the estate was heavily in debt so Dr John gave the job of surveying it to George Campbell Smith of Edinburgh with the remit of dividing a largely unused area up into crofts, of which Jane and John’s originally comprised around 4 acres, so that small rents would be fed into the estate coffers and local farmers could remain. This was around 1840 and part of the idea was to replace the loathed runrig system, where the farmers could be ousted from their small, mounded strips of ground on short notice giving them no stability of ownership or incentive to farm using more modern methods.

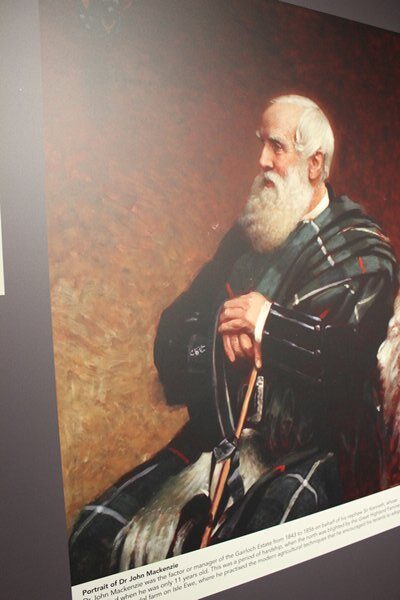

Dr John Mackenzie in 1867, aged 64, after he returned to Inverness having handed over the estate to his nephew, Sir Kenneth.

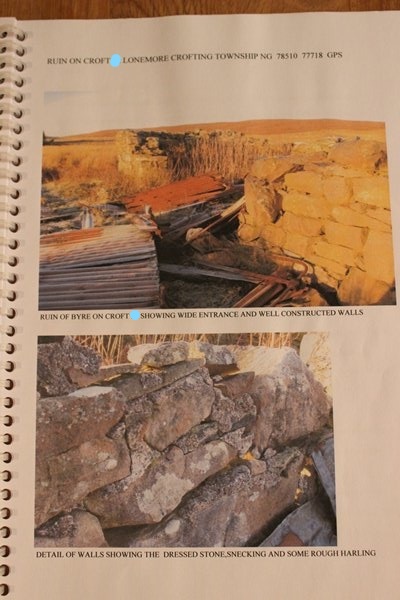

Plans show the old byre and other ruins on the croft and a ditch designed to drain the ground, all of which are still there. A typed sheet refers to the original croft house as being extended and modernised, and there’s more of that to come with modern insulation being installed, and John and Jane have already removed the wall between the kitchen and dining room to make one open spacious room with fabulous views over the loch. I was delighted to be able to tell them of my ‘find’ so they could go and see it for themselves.

We are already looking forward to visiting Jane, John and Pip again next year, on our planned road trip, to see how they are getting on and to explore more of this gem that is Gairloch Parish. We will also find our way to Iona to see Liz and Allan and maybe even make it to the Shetlands and Orkneys. Travelling by car we will not be so weather dependant for reaching the northern islands. In the meantime we now await a weather window to return to the Scottish mainland.