The Long and Ancient Road

We travelled across a bleak landscape of peatlands, too bleak even for pretty cotton grass to flourish, and too wet for gentle cattle, along a single-track road, virtually due west to a period a few thousand years after the end of the last ice age, to where people from Ireland and southern England were starting to settle on the Outer Hebrides and the Orkneys and Shetlands, at this place called Calanais, Chalanais in Gaelic.

Beyond 6000 years ago the area was covered in woodland of pine, hazel and birch and possibly oak and elm, but evidence in the form of charcoal deposits shows the first humans cleared the trees and the rotting vegetation, assisted by climate change to wetter, cooler conditions, similar to today, formed peat beds.

During the times when the climate was warming up, oats and barley thrived along the warm, fertile ridges of soil, known as ‘run-rig’, that farmers had crafted using wooden hoes and spades from the surrounding earth. Where farmers agreed to share their ridges, they could graze a few small cattle and sheep to add variety to their diet, and material for clothes.

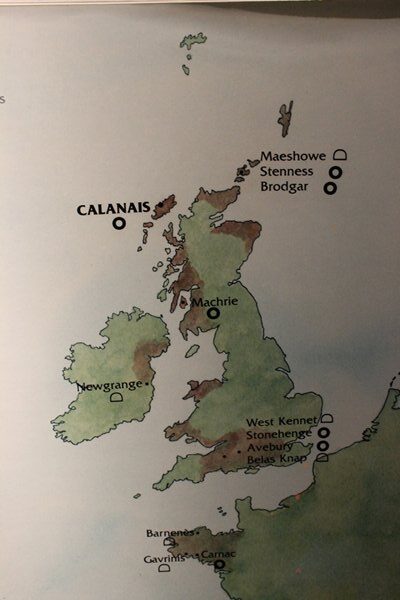

Three thousand years ago, while this farming style was ongoing, and throughout the UK, Brittany and Portugal, stone circles started to grow from the ground under the extensive, and temporarily lost, knowledge of mysterious brains and the might of local men. Naturally there have been many theories as to the why these human creations came to be erected, but how did this new knowledge suddenly come about?

I just liked the above photo, so I thought you might too,

and here’s a little lunar astronomy. Sometimes the circles used solar phenomena instead of, or as well as lunar alignments

We have regained that knowledge over the last three hundred years, so we can begin to see possible answers, which serves more to confirm our understanding of astronomy is not new, than to explain how a small group of human brains back then had that same knowledge of the passage of the sun and moon and its significance to humanity. Did they know each other? Did they travel to places to learn from the intellectual elite and then return to their communities? Places like Lisbon or Egypt perhaps, where the pyramids are the source of similar wonders and research has shown that even the precession of planets, which makes the annual equinoxes earlier each year, was understood by the designers of those desert peaks.

These people lived in closer harmony and inter-dependency with their natural environment and must have been keenly aware of the mysteries of the moon and sun and their irregularities. Knowledge of their workings, the effects of their combined effort on the tides and the passage of the seasons, was a source of power to not only land dwellers but also early navigators plying the oceans.

So, in the case of the Lewisian Gneiss (only 3.0 – 1.7 billion years old!!) Calanais stone circle it is small wonder then if, where the midsummer full moon sometimes skims the mountains to the south, monuments were built to try and capture this power and give it material form on the land.

Just look at that lovely Lewisian Gneiss

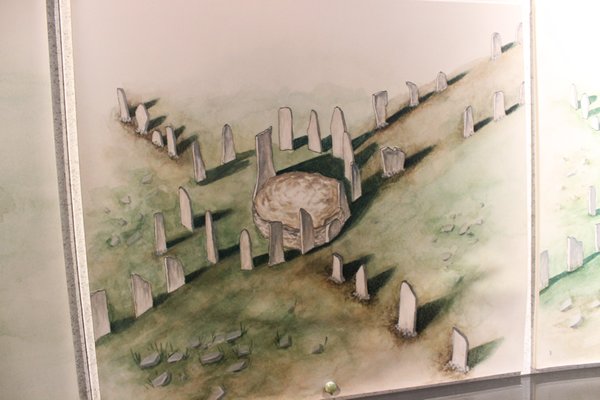

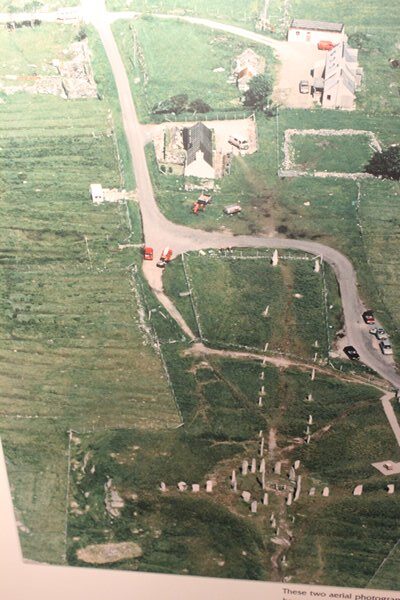

The photos I took at ground level fail to show the interesting arrangement of the stones

But here, left of centre, you can see the remnants of the ‘run-rig’ system

And this one gives an idea of scale

This is the centre of the circle, showing the more recent burial cairn, ransacked many eons ago

The north lying avenue is strangely out of alignment, maybe because of the rock sub-strata?

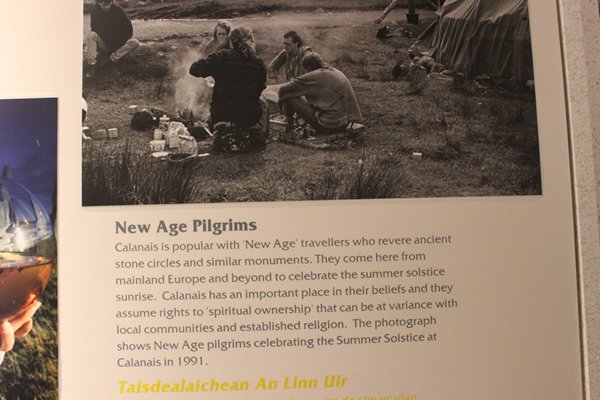

The site is on the pilgrimage calendar for those of a spiritual mind

And for those with more bovine inclinations

At the same time as the building of Calanais, in Orkney, the chambered tomb at Maeshowe has a long passage facing south-west and on days around midwinter, the setting sun shines down the passage to light up the back wall. Similarly at the chambered tomb at Newgate in Ireland the midwinter sunrise shines through a stone ‘letterbox’ above the passage.

It is easy to see why these magnificent sites were also used as tombs, with their celestial connections which determined and ensured survival on earth; where else to bury ones dead but near to a heavenly link, a passageway to the heavens above and celectial bodies that last through time.

A burial cairn was added long after the erection of the stones and was later desecrated

Since the building of the original circle the three single rows of stones on a roughly east, south and west alignment and the double avenue have been erected. Was the emerging shape of a cross just a coincidence to the Christian symbol, or centuries later, did Christianity adopt it just as it allowed certain druid beliefs to merge with the new faith?

Up is north

Since those times the prevailing culture and beliefs morphed to allow the desecration and robbery of some of the stones. That ‘power’ I mentioned either changed or was usurped, possibly by the spread of Christianity. The peat beds around the circle grew to a depth of one and a half metres and were only finally cleared away in 1857, by the workers of Sir James Matheson of Lews Castle in Stornoway, in a wave of Victorian thirst for knowledge, and their study is very much on going.

My head was in a spin as we drove away, passing a lorry loaded with seaweed, heading where? This place holds so many mysteries for the short stay visitor, I was haemorrhaging questions.

The Buried Beauty of Bosta

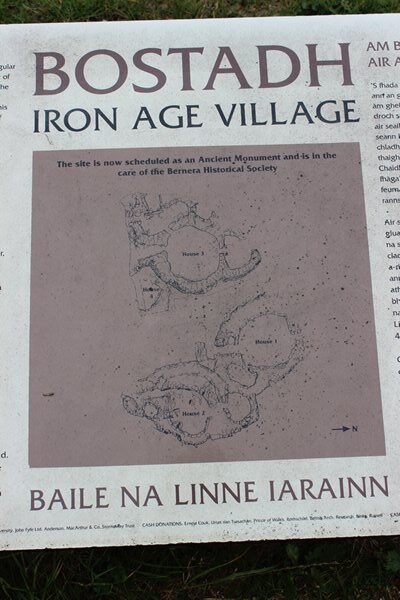

Our little red time machine brought us north westward to the hidden village at Bosta, Bostadh in Gaelic, courageously facing the north Atlantic but within the shelter of an offshore wall of rock, and forward to approximately 400-800AD.

Generations have lived and died in the Bernera area knowing that something special lay beneath the sand in this valley near the sea. Every now and then some artefact would be deposited on the sand, just a tantalising hint of treasures to be discovered when in 1992 a violent storm altered the profile of the beach, and a series of rescue excavations in 1996 revealed an entire village sleeping beneath the sand.

Off-lying rock mounts, a fresh water stream and a fertile valley make this an ideal spot for a semi-permanent village

Five houses were excavated and backfilled with sand to protect them and one remains untouched for future research. So as to give visitors a good idea of what life was like in this Late Iron Age, Pictish Period, a super little replica has been painstakingly built for the purpose of experimental archaeology, and we were fortunate enough to arrive just in time to be shown around by a young archaeologist whose name fails me I’m afraid.

The roof ridge of this late Iron Age home slopes down to the white stick over the small room, possibly the sleeping chamber

Rob rescued this beautiful Magpie moth from a sure fate of drowning that the ancients did their best to avoid as it would have meant the loss of a main provider, plus a loved one of course

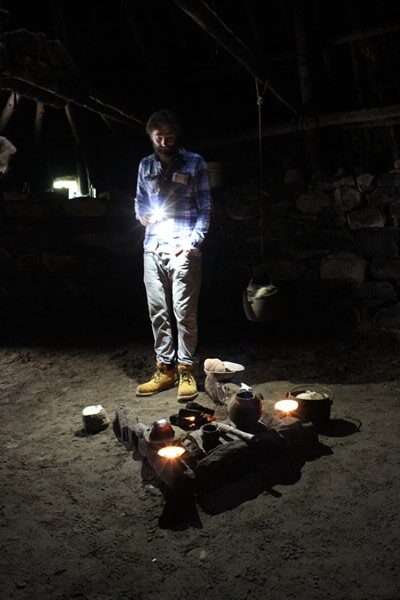

He asked us to give him a few moments to prepare the house for us and when we eventually walked down the curved entrance into the partially underground home we were met with total darkness, until our eyes could adjust to the tea lights he had lit, reminiscent of the animal fat lamps that would have been used, and we could see a bench against the curved wall where we could sit on comfy fleeces for his fascination account of life in those times.

The young man stands by the open edge of the fireplace, where a draft will keep the flames burning

You might just hear the roaring sea while sleeping in there

Even our knowledgeable guide was not sure what the upright stones in here were for. Maybe to dissipate the draft in this enclosed area

The houses all have common features; double walls, they are semi-subterranean and have downwardly curving southern entrances, away from the cold north winds off the sea and to allow warm sun lit air inside. Each have a main circular room with a central stone-lined hearth. Our charming host explained that the stones were on only three sides of the hearth, with the empty side exposed to the draft from the door so the room had a cool and a warm side for reasons of storage and comfort.

We descended the curving south entrance into total darkness

Another small room or ante chamber led off the main room and could have been used for, well you can guess; storage, sleeping, privacy. The roofs were made of timber thatched with turf and only the top of the walls and roof could be seen above ground. The sloping ridged shape you can see in the earlier photo allows for the building of the small ante room and is typical of the late Iron Age and is the precursor to the early blackhouses.

This was an ideal location for the village within the sheltered bay that provided sea-food and grazing for sheep and cattle. In the vast midden along with seashells and animal bones, including those of the domestic animals, were red deer and wild boar bones, suggesting the presence of nearby woods. A healthy diet for all.

Apart from farming and fishing the families also practiced pottery making, weaving, boatbuilding and leatherworking and of course teaching these skills to the next generation. Busy times.

Our ruddy time machine sped us on to the remarkable little Uig Museum where I photographed a brilliant time line for future reference and then to the empty white sands around Valtos and Miavaig, before returning to Stornoway, fully aware that we had only seen a fraction of the history this remarkable area has to offer, for an evening with fellow cruisers and in anticipation of our last day tour, this time southwards.

Vast, pristine and empty beaches abound in the Outer Hebrides