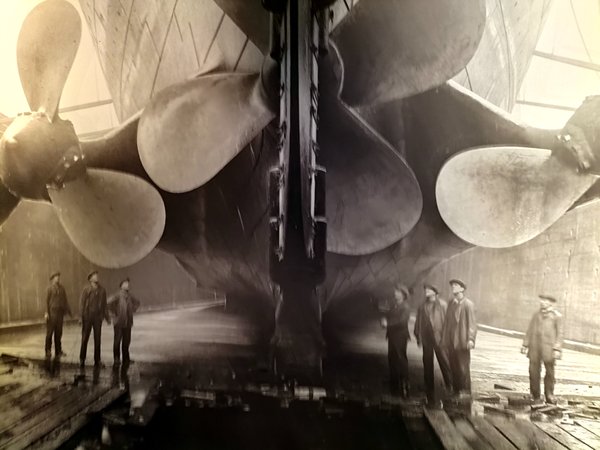

Men in Cloth Caps

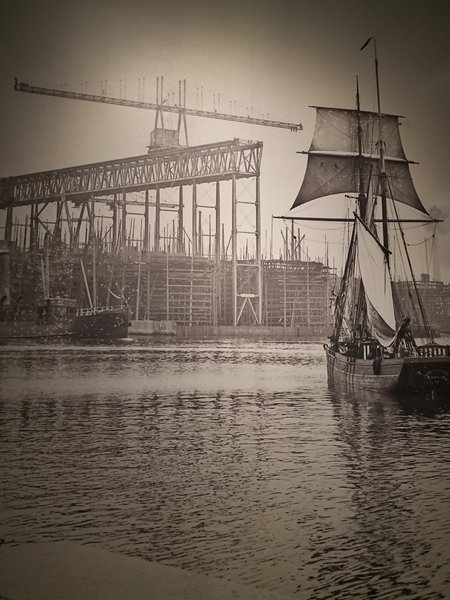

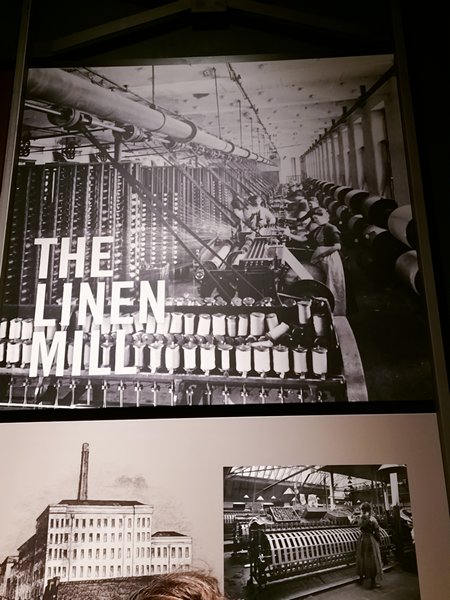

‘Health and Safety’ were not around when the shipbuilding industry in Belfast grew from 1663 to be the fastest cargo discharging port in the world. Using both manpower and cranes to move the goods and support the local industry, including linen, which by now (1907) had moved from being a cottage industry in outlying villages to factories within the rapidly growing city.

Over 6000 cloth-capped dockers worked on a casual basis and in all weathers for up to 68 hours a week on low pay. Many fell into the River Lagan and others were crushed.

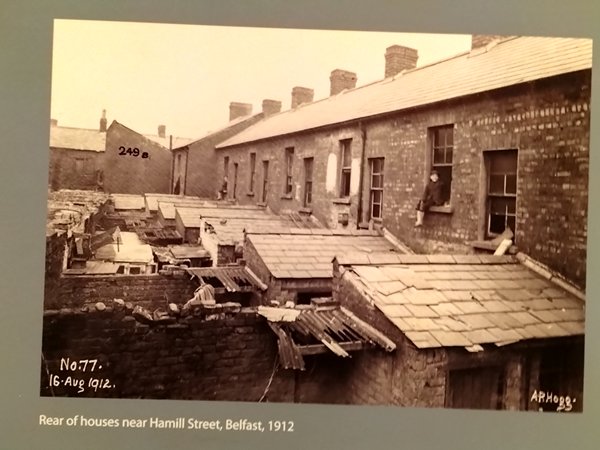

Even their strike in 1907, supported by the police failed to improve conditions for them. They lived in back-to-back tenements, overcrowded and with no thought for their mental or physical health from their bosses.

Yet their pride in what they were creating was as evident at the time as it is now. Where did their feelings of satisfaction in being a part of these cutting- edge vessels come from, that have survived to this day through the testimony of their families?

Having moved from rural backgrounds, where the sense of community was strongest, in their need to survive and provide, these men had a strong code of living that meant they had to trust their fellow workers, their friends and ‘brothers’, which they transferred to working on these new advanced and luxurious ships. A new kind of survival was needed and I imagine there was a strong working community living in Belfast, so ironically in a sense their team spirit if you like, from their pastoral days, was preserved in their new tough lives.

There are video accounts from two young ladies who talk of this pride in the involvement of their past relatives, (a grandfather and great grandfather I believe) which makes them feel pride in their forefathers and they firmly believe should be remembered by their future generations. A preservation of community values in the modern age.

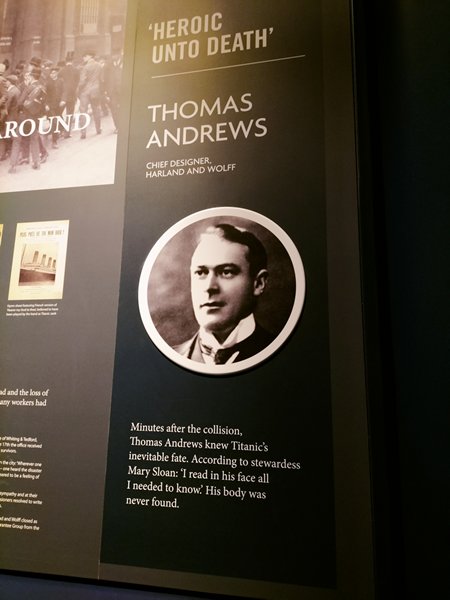

Imagine how Thomas Andrews, who took over completion of the project to build the Olympic Class liners felt, (after Alexander Carlisle, ‘Big Alec’, the actual designer resigned in June 1910,) when he knew minutes after Titanic collided with the iceberg, three days and thirteen hours into her maiden Atlantic crossing, that because it was the side of the ship that was ripped open beneath the level of the bulkheads, there was only one possible outcome for her. Had she hit the berg head on, where the bulkheads were built higher, the tragedy would have unfolded differently. He advised passengers to dress warm and be ready to abandon ship. The responsibility on his shoulders must have been indescribable; a mercy perhaps that he did not survive.

The Titanic Museum itself is an amazing design which inspires the imagination, an iceberg to some and the Titanic bow to others; and the surrounding area has been cleared, with the outline of the Olympic and Titanic marked on the ground in thin white lines where they were actually built, is thought provoking. Add to that vision the visual and literal displays inside the building, then one can sit and let the mind wander to the 3D shape of the liners, as they grew upwards through the immense and brave efforts of human hands. Add the noise and hardships, all types of weather and temperatures and one can get some idea of what it was like, back then.

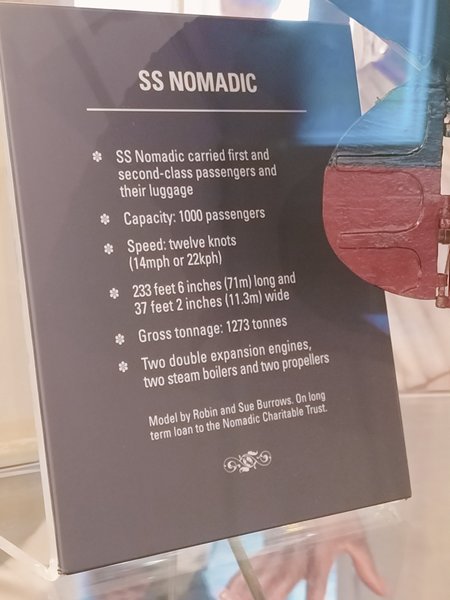

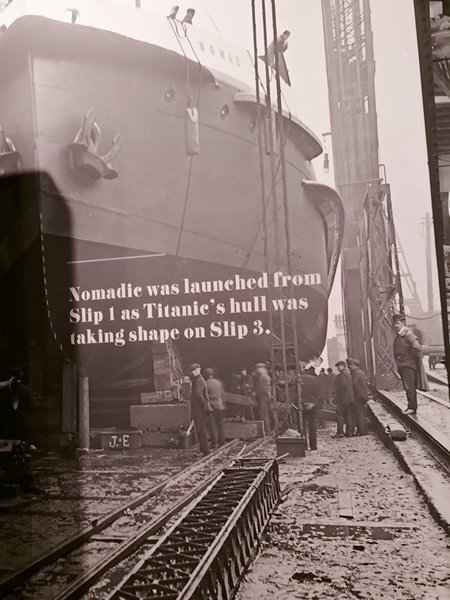

The beautifully restored tender to the Olympic class ships, SS Nomadic, fronts the museum. She is the last remaining White Star Line ship

You can just make out the white lines, the bow ending to the left of the pair of blocks at the bottom of the photo

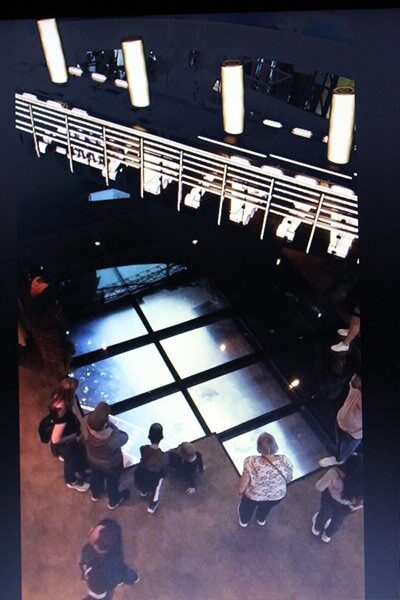

Even the triumphant discovery of her wreck lying on the seabed by Jean-Louis Michel and Robert Ballard was immediately tempered to show due respect to the status of the site as a mass grave. But within the museum we are able to experience this moment in a multi-storey gallery where Rob and I stood on the top floor. Just in front of us a hollow, illuminated and suspended model of the ship turned very slowly around above the heads of visitors who were peering down through a virtual window to see the footage of the discovery of the wreck by their RV Argo.

The gallery is dimly lit with classical music playing and I’m afraid my camera could not pick up the detail of the wreck, but the atmosphere was thought provoking

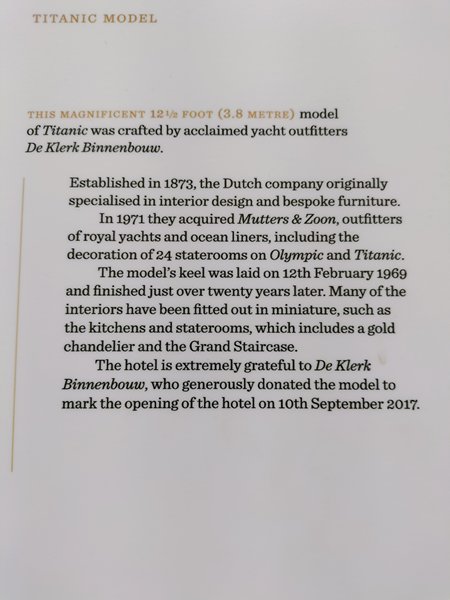

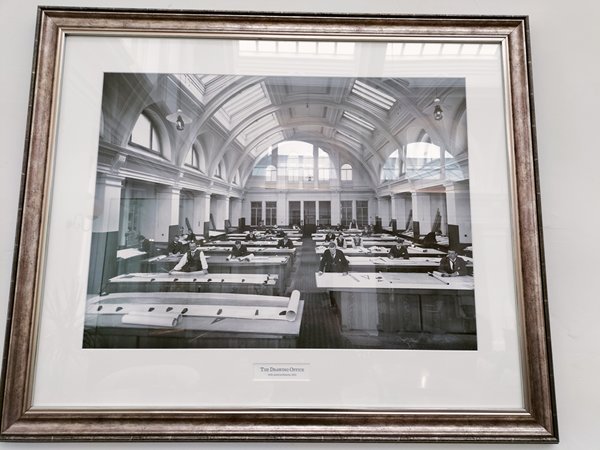

If you really want to see what the Titanic in her completed form looked like, showing her fabulous corseted feminine lines, and even a solid gold stairway chandelier, then there is a fine model of her in Drawing Office Two of what is now the Titanic Hotel Belfast. We had been recommended to visit and had a coffee in there before going in to the Museum itself. I was reminded how my grandfather, George Astell Hall, was a marine architect before WWI, designing gun turrets for warships. I wondered if his drawing room in London looked anything like this one.

Just look at those lines!

The foyer of The Titanic Hotel

Drawing Room Two back in the day

One remaining tangible reminder of the Titanic is the SS Normandy who worked as a tender, transporting passengers from the too small and shallow Cherbourg quayside to the massive ships. Her life has been a long and interesting one and now anyone can board her in her faithfully restored state on exactly the spot where she was built in readiness to serve the Olympic Class liners.

First and second class passengers were accommodated on the Nomadic

The crew cabins were up for’ard

The fo’csle in the bow was used for storage

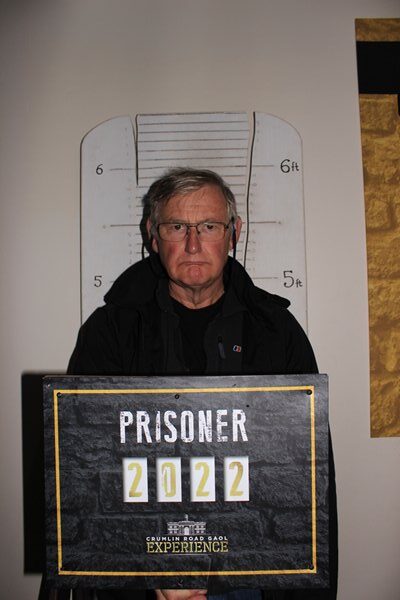

The Crumlin Road Gaol Experience

In 1716 the Banishment Act set the ball rolling for criminals to be sent to North America and later Tasmania and Australia, relieving the pressure in the Irish gaols and boosting the colonising spirit at the same time. Three years later another Act reaffirmed Britain’s right to legislate for Ireland. Up until 1867, when the Transportation policy ended, 50,000 to 60,000 mostly poor and illiterate men and women had been banished from their homeland.

The gaol was built between 1843 and 1845 and many of the inmates destined for transportation to the new colonies on charges of larceny, (theft), arson and house breaking, some as young as 10, died in the prison, how I am not sure.

In 1849, when 88 male and 30 female prisoners were languishing in the gaol, a tunnel was built connecting the courthouse to the gaol and I can tell you I would not like to go down there at night.

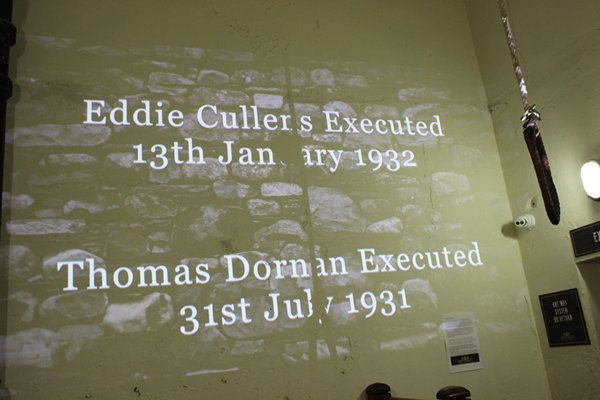

I remember hearing the name of the gaol on the news during the troubles from the 60’s to 1998, when the overcrowded prison numbers reached 1400 in a prison designed for 336. Before then, from 1854, seventeen hangings for murder took place in the Execution Chamber and it felt strange standing there where the last man, Robert McGladdery, was executed just before Christmas 1961.

Corporal punishment using the birch rod and cat o’nine tails took place, controlled by rules from 1922 to 1968. Presumably before then the punishment was at the discretion of the governor.

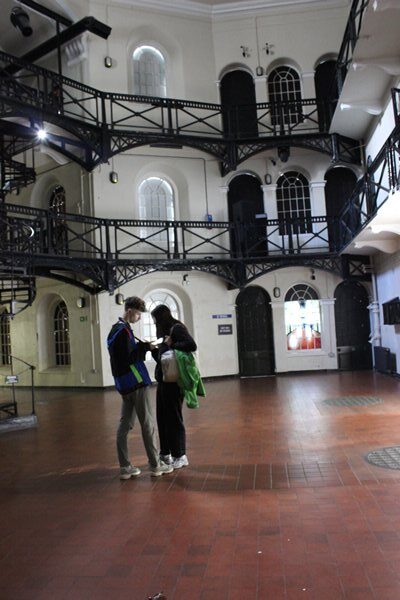

Surprisingly, despite it being a harsh place to be, the gaol was not devoid of artistry. Two cells had been knocked into one so that art classes could be taken, and the then governor gave permission for the walls to be used. Also, in the design of the infrastructure curved wrought ironwork gave a break from the regimented straight lines of the cells, all the same I’m glad we were only visiting!

Having been cooped-up for a few hours, some fresh air and distant views were needed. A roof-top bus tour sped us around the city and along the Falls Road, where wall murals bare witness to the religious/political strife of the recent past.

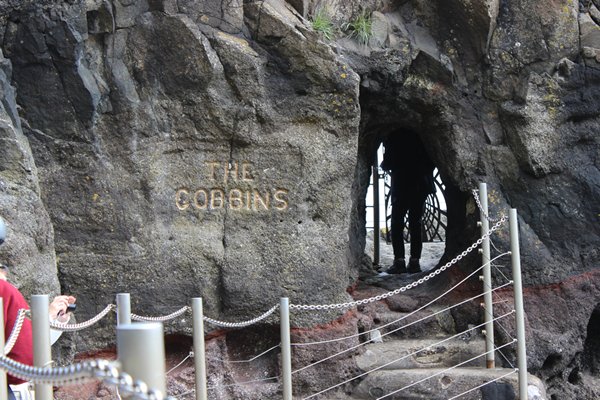

The Gobbins

On our way down the coast towards Bangor Rob noticed a walkway, suspended close to the water on the cliff edge and we decided it required exploration.

Not having access to a car, we worked out how to get there using two buses and then a lengthy walk to the modern centre and car park. We crossed a bridge over the same stretch of water where we had precariously moored Zoonie.

The first Gobbins Path was built in 1902, having been designed by the Chief Engineer of the Belfast and Northen Counties Railway Company, Berkeley Deane Wise; a decade before the Titanic disaster and in the same year one desperate soul escaped from Crumlin Road. Within a short time, the ‘walk’ gained worldwide fame, but it was expensive to maintain and was closed for a time during WWII and then again in 1954. Wise’s original floating bridges and his iconic Tubular Bridge fell into the sea, but their bases are still there, embedded in the rock for all to see.

Renewal took place and today’s hovering path opened in 2015. We walked in single file behind our guide, Nina and had to stand at the side for groups coming the other way to pass us. I had to take pictures on the move so as to not stop the people behind me.

The close proximity to the water was delightful and the terrain was rocky and steep in places; a really good workout, with great views of our favourite elements, the sea and coast, but I did wonder how the first ladies got on in their crinolines.

There were lots of Kittiwakes, guillemots and razorbills to see, on their nests looking after this year’s young and pooping in flight. We huddled under a Perspex roof at one stage to avoid being hit by avian epaulettes. Despite recent inclement weather we had a perfect day for the romp and by far the hardest part was climbing back up the hill to the road.

This is a replica of Wise’s famous Tubular Bridge that fell into the sea

A Bargain in Bangor

As Rob and I were planning to take out an annual mooring contract at the Boatfolk Marina in Portland at the end of this year’s cruising, and Bangor Marina is one of the Boatfolk groups marinas, we asked if our time there could be taken out of our first year’s allowance of free berthing in any one of their eleven marinas. The kind manager checked that we had been in contact with Portland and allowed this and we were most grateful.

The marina itself was a friendly place and wandering around the town brought more delights in the form of a sugar cube model of the Town Hall, a relaxing time in the lovely Bangor Castle Walled Garden and down near the harbour the 1637 Tower House built as a customs house with a defensive tower next to it for protection in turbulent times, but with today’s visitors being more friendly the house part is now home to the Visitor Information Centre and offices.

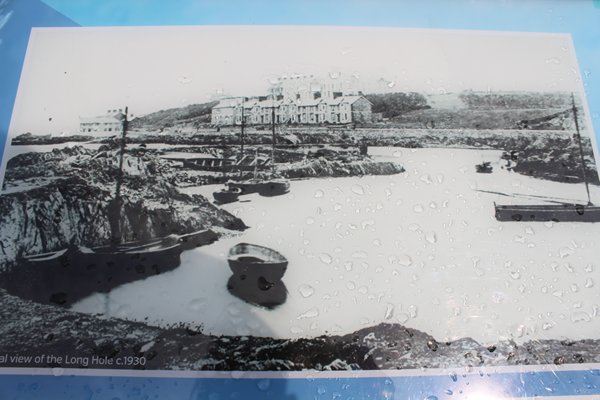

The old harbour is lovingly referred to as the long hole, a place of natural shelter from the weather outside the estuary. We saw it at low tide where it seemed any vessel moored in there would have to sit on the bottom. Today it is a handy place for people to safely relax by the water and maybe do a bit of fishing.

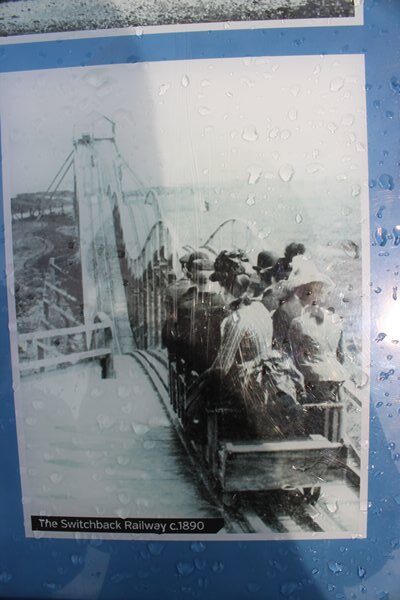

In fact, for many years Bangor has been a place to play and the switchback railway built in 1890 was just one example of an aid to leisure. It only lasted four years before a storm in December 1894 destroyed it. So Wise’s Gobbin’s Cliff Path, opened in 1902, must have been a welcome distraction over the water.