Part 2

Tolsta and the Bridge to Nowhere

Our second day brought a submersion into gorgeous coastal views, crofting history, Victorian industrial zeal, and ancient Christian activity leading to the downfall of the MacLeods and the gifting of Lewis by King James VI of Scotland to the Clan Chief of the Mackenzies in 1610. A heady day of history and scenery that I will try and make enjoyable for you.

Driving to the far extremity of our day’s adventure, so we could work our way back, we arrived at the Garry Bridge; a robust concrete structure, the idea of Victorian entrepreneur, Lord Leverhulme, (of Sunlight, Lux and Lifebuoy soap fame) who owned the island of Lewis from 1918 to 1923. He had planned to link Tolsta on the north east coast to the lighthouse at the Butt of Lewis where we had been the day before, but his plans were thwarted when the soldiers returning from WWI wanted long promised croft land for farming and not employment from this ambitious lord whose idea was to industrialise Lewis and turn the locals into employees. So, the road was never completed beyond the bridge, although one can walk the distance on a strenuous hike. Not for us, as we had a lot to cover in one day.

Ever onwards

We drove back down the road we had come along, past sunken rectangles of peat beds last worked nearly two hundred years ago, before the area was cleared, to a little car park, so we could take the time to explore the beaches and soak up the rugged views.

Disused peat beds in an ongoing practice elsewhere

A freshwater pond full with flowering waterlilies and grazing geese

Lovely machair grass protects the sand dunes

Pristine deserted beach; one of many

You remember the blackhouses I mentioned in Part One? Well from the early nineteenth century croft houses were built to a different design, with pitched roofs over double skinned and cement bound stone walls, but with windows and fireplaces. Reformers of the time including Leverhulme and the government inspectors considered ‘blackhouses’ were unsanitary and unfit for human habitation. They appeared blind to the fact these sturdy, low, well insulated homes had been ideal protection for people and animals for a thousand years.

The new builds were referred to as whitehouses to differentiate them from the blackhouses and many whitehouses still exist, and with modernisation, make excellent, durable homes. The ruin we came across was, as you can see, built by a G. Mac…. in 1826 and was lived in by a family with likely at least four children until 1851 when the area of Tolsta was cleared and the inhabitants left aboard the Marquis of Stafford for Bruce County in Canada. The turmoil and human pain this must have caused is hard to imagine and of course it all came to a head later on.

The little birds that kept a close eye on this curious couple poking about the shore around Tolsta are Northern Wheatears and fortunately are of least concern on the survival stakes.

A Recent Marine tragedy

You may have heard recently of the tragic beaching of 55 Pilot Whales on Traigh Mhor beach. I took this photo about a month before that disastrous event. The matriarch of the pod was having difficulty giving birth, and being highly social creatures, they were not going to let her go through this alone, so they followed, many other females giving birth at the same time. Not only was the whole pod wiped out but the entire next generation as well. Heartbreaking.

We walked down a good path to the Iolaire Memorial that overlooks the site where this broken ship rests on the sea bed, but more about that later as there is more to the story within Stornoway itself.

Ui Church near Aignish

Instead, our last call was made to the current Ui Church of Columba at Aiginis; a misnomer in the sense that St Columba never came there whereas a disciple of his, St Catan most likely did live in a cell there for some time while spreading the word of the new Christian faith throughout the region. He also became bishop of Bute and was renowned on the mainland as well as the islands.

On his arrival in the area from Ireland in the sixth century AD he would have come across farming communities who had already been gleaning lives from the land for four and a half thousand years, raising sheep and cattle, growing cereal crops and fishing mostly shellfish, judging by the contents of their extensive middens and following their own faith, possibly Celtic polytheism, a loose blend of druidism, paganism and other sects.

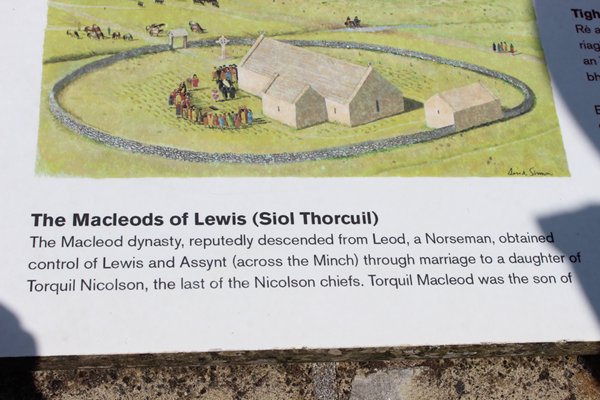

Sometime between the occupation by the Scandinavian Norse Kings from the early eighth century until 1266 and the uniting of the islands when John of Islay became the first Lord of the Isles from 1354, to the end of the 14th century the first church was built on the site, and since then numerous alterations and additions have all but disguised the original building, the remnant of which can just be seen in the north wall.

Knowledge of the presence of the cell of St Catan must have been handed down for more than 600 years by word of mouth, and the religious significance of the place preserved until the first church was built. The area is in the process of being explored and maybe there was a church or chapel even earlier than the present one.

A better idea of what the church once looked like

The Eastern Chapel where 19 MacLeod Chiefs, amongst others, are buried

Originally the church was built well inland but coastal erosion means the local community has worked hard to create sea defences to protect the present building. They also had to re-inter some bones after locals saw them being washed away on a high tide, maybe those of St Catan himself.

The church is particularly significant as a burial place of nineteen chiefs of the MacLeod clan up until and including Roderick MacLeod X in 1595. After a tempestuous career of feuding with the locals and the Scottish crown for 46 years he effectively lost his clan their rightful inheritance. Matters were taken out of his hands and the independent sovereignty of the isles was over.

The graveslab of an earlier Roderick MacLeod the 7th, depicts him as a warrior and is now protected beneath a modern canopy roof

This sandstone marker shows symbols typical of the Knights Templar

Thanks to James VI of Scotland, in 1610, along came the Mackenzies, Kenneth of Kintail to be precise. Phew, I hope you’re keeping up! It’s quite crowded underground within the tiny building, especially with the addition over the years of MacKenzie chiefs as well, and just imagine being the priest who used to live within the walls and keep warm in front of the fire, chatting of an evening with the MacLeod ghosts.

The Fight for land and a way of life

Nearby is the 1995 stone split cairn memorial on the hill outside the cemetery, commemorating the Aignish Farm Raiders’ fierce standoff between landless locals, and police and marines armed with bayonets sent to regain a farm that locals had seized control of in January 1888.

The raiders were driven by poverty, inequality of land ownership, and anger at the defence of wealthy landowners by the Government. This was part of the ongoing Crofters War which eventually led to land reform. Of the many brave locals who took part, 13 were imprisoned. Crofters wanted a subsistence way of life by farming their own land, plus casual work to supplement their income. They did not want to lose their independence and become employees of over rich landlords. I don’t blame them, what they were doing was sustainable, efficient and modest.

Seven years later the farm was rightfully divided into crofts and given, as promised to local farmers to become self-sustaining small-holdings of around 4-acre strips. Today crofts average 12 acres. Many of the raiders had died by this time, coining this verse on the memorial;

Many of them sleep below

This ground they hoped to gain

The pity is they cannot know

Their raid was not in vain.

Modern Scottish crofting laws state the owner must be ordinarily resident on their croft, or within 32 kilometres of it, must not misuse or neglect the croft, and must cultivate it or put it to another purposeful use. Crofters have the right, subject to planning permission, to build a house on their croft if there is not one already there and we saw a few modern blackhouses looking out over their strips of land. These days crofts can be used for any form of husbandry, including planting trees, keeping and breeding of livestock and growing fruit and veg; so, the independence of the crofting way of life is protected by laws as robust as the greenhouses some of the crofters use for growing their crops.

If you go onto Google Earth to the island of Lewis/Harris you can clearly see the thin lines of the ‘rig and run’ raised ridges of agricultural land and the more recent slender long strips of the crofts properties.