The Perfect Wind For Our Voyage South

18:20.41S 178:18.53E

Zoonie crisped along at 6.5 knots with the wind 60’ from her port bow on a course just west of south, 212’ enabling us to sail between Beqa and Kadavu Islands. The wind was a generous 18 – 20 knots and the bow wave washed the very muddy anchor clean in no time. Lisa had waved ‘bye’ as we left the anchorage on October 13th and fearless surfers enjoyed riding the steep waves as they broke on the seaward wide of the reef at the entrance to Suva Harbour.

A few hours later we prepared for the night by reefing Zoonie well and losing nothing in speed in a wind that was showing all the signs of being on the make.

By watery sunrise the wind was filling to 27 knots as Zoonie entered the uncluttered weather arena of the sea between the South Pacific Islands and mainland New Zealand. The water beakers that stand in their wooden holder just infront of the compass in the cockpit were rimmed with salt from the flying spray; drinking from them we tried to imagine we were drinking Margaritas without the bite.

At night the stars gave way to dark scudding banks of cloud, but they were mostly innocent of sudden strong winds, the steady Tradewinds were hogging the skies.

Zoonie would lose her footing in a sudden trough opening beneath her and the wind would shove her 45’ to leeward, the pull of the genoa and her buoyancy helping her regain her stride ever forward. Progress was good but not without a little discomfort. After one deluge of water into the cockpit, soaking the cushions and us, we retreated into the peace of her saloon and watched the proceedings from behind the glass windows.

By the next day, (22:05.14S 175:55.32E) the 15th the wind was a full 31 knots and Zoonie pounded the waves as they pounded her back sometimes with such alarming bangs on her topsides you would not think could be made by liquid alone. White veils of seawater erupted from beneath her bows and went her entire length blasting her big windows so vision through them was made perfect by the total water film covering them. I remember wondering how long that amazing foresail would last, constantly pulling 13 tons through the water and holding tight to the full Force 7.

Henry, the wind self-steering gear was doing a valiant job. As a gust suddenly knocked Zoonie off course, the genoa would flap and the combined force of Henry’s rudder and Zoonie’s natural tendency to come to wind would lure her back onto course so the genoa could fill once again, in an act of inanimate teamwork that we mere mortals below truly appreciated.

As I rested in the down side berth I looked up at the tons of white water ploughing down the side-deck above my head, at times we were almost submarining. You can really feel her movements when relaxing horizontally and not having to hold on. Zoonie would sometimes lift over a wave and be suspended for a fraction of a second, her front half flying in the air and I’d think ‘Oh, oh, there’s only one way from here,’ and down she’d come sometimes to a soft landing but very occasionally to a thump that shook her to the keel.

Rob was amazing, he’d have to go out on deck in the wild weather, once to unjam the Furlex reefing drum right up at her bow, another time to tighten some halyards which had stretched from being saturated and vibrating constantly. He’d go out just in his briefs because he knew he was in for a drenching and would return down the companionway ladder glistening top to toe in seawater.

We would both venture into the cockpit to reef or ease the genoa and on this day as we did so we both saw at the same moment the 6 inch seam tear near the luff of the genoa. Zoonie’s lovely 6 to 7 knot progress was under threat.

An Orange not for eating.

“We’ll roll it up completely and I’ll set the storm jib” Rob said straightaway. In the calm of Lami Bay he had already re-positioned the inner forestay from its out of the way rest position on the coachroof and attached it to the eye on the centre of the foredeck ready for action. The jib was hanked on ready and the sheets taken down the side decks to the cockpit. So all that was left for him to do was to hoist it while hauling on its halyard at the mast base, but of course Zoonie was moving a fair bit so it wasn’t easy. As the little orange sail rose I tensioned the sheet to stop it flapping and then, when the halyard was taught, winched the sheet so it pulled, but oh dear we were down to 3 knots of speed.

By this time the companionway steps, handholds and floor had a thin layer of seawater spray all over them that made them as slippery as ice and I kept thinking I needed to wash them so they could dry.

Down below life went on. By this time both the wooden wash boards were in place and the hatch cover was fully closed and it was just as well because waves were now breaking over her stern port quarter and making it into the cockpit where it drained, too slowly in my view, down the drains.

Suddenly there was an alarming crash as a ton of water hit the washboards. Not a drop came down below but I watched from a head sized slit I made between the hatch cover and washboard as the blue/white liquid mass swirled around the cockpit floor, washing the portholes and making the steering column up to the wheel look like and island or a windfarm generator.

Talking of which our wind generator plus a little daytime UV on the solar panels kept the batteries charged to 100% with over 13 volts and if you know nothing about electricity, that’s good, in fact it’s perfect.

Our hands were becoming sore from gripping the slippery handholds so tightly, and we wondered if anyone else had taken the same perfect weather window as us.

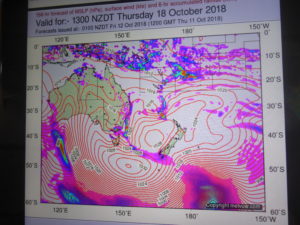

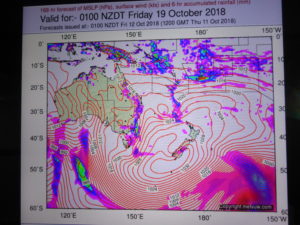

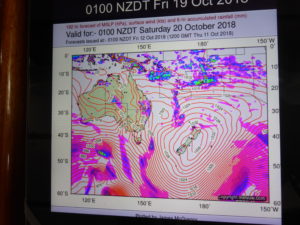

Checking our two weather forecast sources in the five days before leaving we had seen this massive High sitting almost stationary over a vast area and there was not a Low in sight. The pattern did not fit our previous knowledge but it clearly wasn’t lying to us. Favourable easterlies would blow for the next 10 days at least. That along with Jon Martin’s sound advice to take the first weather window we see was enough for us. We knew that Pebbles was planning to leave two days after us but she was taking a more westerly route to the Wellington area. Was there anyone else out there?

Zoonie Changes her Rig.

I didn’t like our reduced speed and neither did Rob or Zoonie. “Babe, what about unfurling just a little genoa, up to where we can let the split stay in the furled part,” I said.

Well Zoonie showed her appreciation by surging from 3 to nearly 7 knots in the 30 knot wind and that’s where she stayed for days to come. Effectively a cutter rig, all her sail area kept nice and low with the genoa the size of a single sheet and the mainsail with its third reef in, more to steady the hull and allow maximum flow around it to the foresails than to provide much drive and the smart, tough little storm jib enjoying the company.

Zoonie starts Across the South Fiji Basin

23:35.19S 175:28.02E

Our bodies were aching from bracing ourselves inside Zoonie as she ploughed on with determination on her own route direct to Bream Head off the Whangarei River, despite our trying to keep her on a southerly course for 30’ South latitude and due north of North Cape. The chances of a Low passing across north New Zealand, while we hung about at Lat 30’ was decreasing as the days went on. This magnificent High persisted and resisted any encroaching systems.

My written notes are hard to read and reminded me of the illegible scrawl of the Dental Advisers that I learned, by the process of de-coding, to decipher at the Dental Estimates Board in Eastbourne where I worked briefly in a past life.

The forecast showed more of the same bountiful wind supply with possibly a brief reprieve in which we hoped to tidy up and wash the woodwork clean of salty moisture.

The reprieve didn’t come. We were just starting to move over the flat seabed, or abyssal plain, known as the South Fiji Basin so I wondered if this factor might reduce the tempestuous sea. It was running at 5 metre swells and moderate waves and was unlikely to lessen until the wind did.

I take a tumble.

At 10.45am or thereabouts I was standing on the third step of the companionway keeping an eye on Rob as he adjusted Henry from the back of the cockpit when, with a suddenness we had not experienced before Zoonie was yanked sideways by a marauding wave just looking for mischief, the sort that can open up the seams of a wooden boat. My hands lost their grip and I spun around and off the steps, hitting the floor on my back and slid head first down the 11 inch step into the chart-table footwell as Zoonie pitched upwards. A loud crack and then, mercifully it all stopped. I had something broken on my chest, ‘Have I broken my glasses’ I thought, but the shattered pieces of plastic where white. My skull had smashed the double three pin power socket to smithereens.

I feared I might have an injury or injuries that would render Rob single handed as I slowly sat up, checking for snapped bones. But all seemed well as I dragged myself up to a sitting position on the cabin floor leaning against the seat front.

That morning I had dressed in a fuchsia coloured t-shirt which was handy because I noticed blood dripping onto it and thought if I had worn a white one the dramatic effect might have caused me to faint, like I did when helping my brother de-horn a young animal and a spurt of blood shot across the stable and down the white wall. I can taste the metal sensation in my mouth just thinking about it.

Rob came down the ladder, his task complete, “I’ve had a tumble” I said somewhat obviously. Rob was alarmed and concerned, “You could have broken your neck!” He said while parting my hair to inspect the cut. “It’s not very long, so I don’t think I’ll need to shave your hair and apply steri-strips.” Did he sound a little disappointed? He tended me lovingly mopping up the mess with antiseptic wipes and words of encouragement while I was feeling the golf ball sized bump swelling rapidly on the other side of my head.

The incident meant I had to spend the morning recovering by languishing on the leeward settee like Venus de Milo while Rob administered mugs of coffee laced with rum, flapjack and squares of Cadbury’s.

By the afternoon I was back in harness, no stuff and nonsense on this boat! Surprisingly the wind was easing down to the low 20’s and the sea showed the signs of smoothing as well.

Earlier on we were startled when the bilge pump alarm went off. Checking underneath the sink at the lowest point of the bilge Zoonie had around one foot or a gallon of water swishing about. A quick taste check confirmed it was sea-water. When the waves were at their height and filling the cockpit Rob discovered that the rush of water was filling the two small open side lockers above the cockpit seats.

In each of them were air vents and a few times seawater was being forced through the vents, along the headlining beneath and running down the wood beside the chart table and down the wooden headboard above the sink. We had never had this happen before and judging by the permanent stain the sea-water trickle left on the wood, neither had Zoonie. The paper charts were acting like a sponge, but no worries there as they are Admiralty and designed to dry out many times. Rob stuck duct tape over the openings and over the speakers in the cockpit.

Not only that, but Rob suspected a seeping of sea-water along the starboard side of the side deck between the teak planks and the scupper. He has re-caulked the port side deck because it had failed in places, so that went to the top of our ‘to do’ list. Climbing into the cockpit to man the hand bilge was done when we were up there anyway.

Zoonie was still creaming along and I was thinking what good practice this was for the Indian Ocean which by various accounts is another windy passage. Approaching 30’ north it was becoming more obvious that Zoonie was right in trying to head direct for Bream Bay. There was no Low to worry us so we allowed Zoonie to have her way. We rarely record 7.3 knots speed.

Five days out we noticed another split in the genoa between the sunstrip and the white sail material, leading us to think the fabric was failing as well. “We’ve got the spare genoa on board, why don’t we take both foresails down and rig that one.” I suggested.

To do this lengthy job we both needed to be on the foredeck while Zoonie motored under the autopilot head in to wind so as to minimise the motion caused by the moderate sea state.

The storm jib was unhanked and stowed and the inner forestay re-positioned in its home leaving the foredeck nice and clear. I pulled out the tired genoa so we could lower it down the forestay, me easing the halyard and Rob pulling it down. I dragged the foot along the side deck so it could be folded like a fan from each end and then rolled over itself towards Rob and bagged.

This bagful replaced the one containing the spare genoa, which we have never used and which we keep under the dining table on passage along with the spinnaker to bring some weight back from the bow.

I then stood infront of the forestay so as not to get knocked by the flapping sail and fed the sail up the roller reefing groove as Rob hauled on the halyard by the mast. It was lovely out there. Bright sunshine glistening on the beautiful sparkly waves under a clear blue sky. Shearwater birds swooping low over the waves completely dis-interested in us.

We were delighted at how white and perfect the spare genoa looked as it rose up the forestay. It was clearly a light weight one with thinner seams and only a single row of stitching along them, so we wondered at what max wind speed it should be stowed. Later, Phil at UK Sails in Whangarei suggested 15 to 18 knots. Oops, well we flew it at 14 to 22 knots so that was a test for it but we did anticipate a declining wind force which was already happening. The whole pleasurable exercise too only 45 minutes and brought Zoonie back up to 6 knots.

The volume of spray was replaced by a chill in the air and we had to hunt for warmer clothes and our slippers! But things were getting easier down below as Zoonie sped along on an almost even keel in a half metre swell and we could walk around without looking like gorillas. Porridge and coffee infused with a tot of rum was called for and my mind was turning to the big bake I would need to do to ensure Customs New Zealand would not confiscate any of our food.

At night we could wait for the change in watches to reef and ease the genoa. Rob would haul in on the reefing line as I let out the sail under control. Then as he stowed the line I would do my best to tighten on the sheet as Zoonie pitched down and it slackened until Rob arrived and spun the winch handle as if making tomorrow’s pancake batter.

Approaching latitude 30’ I must have been tired because I read 6.30am on the clock as if it was the compass and thought how nicely she was heading Due South!

66.6666666666666 hours recurring.

We had 400 miles to go to the waypoint off Bream Head and at the current speed of 6 knots it would take us the above number of hours to get there. Zoonie broke her speed record that day with a run of 152 miles and a maximum of 8.1 knots briefly. Without a swell and heaving waves to impede her progress she sped along.

Relief permeates the atmosphere on board and as we laugh and joke over the smallest thing we realise how tense we have been over the past few days in anticipation of this historically tricky crossing. Now the end is in sight and although we never take anything for granted and try not to tempt providence while at sea we really started looking forward to our arrival after one of Zoonie’s finest sails.

A Perfect 1000 Mile Beam Reach (32:11.07S 174:40.21E)

On the same day that Zoonie achieved her record beam reach we were greeted into New Zealand waters by a single Albatross gliding around us for a few minutes in which time it did not flap its wings once. I emailed Customs to give our position and ETA.

The previous night I dreamed that I was interviewing Jamie Oliver, sitting infront of the log fire in his home when he leaned forward and kissed me on the forehead.

His face changed into Rob’s, “We need to put the engine on love, wind’s down to 4 knots and falling.” My hopes of flying the Diva as the wind backed to NE were dashed, there wasn’t even enough wind for her gossamer gown. But it did make galley work easier. Also the cockpit was dry now so we sat up there for the hour before sunset and had some interesting discussions over gin and tonics beneath the latest washing.

“As the old genoa has thrown its sheets to the wind we could use the fabric to make anoraks for eachother,” I thought inventively.

“No Barbara” notice the use of my full name. Rob knows I feel I’m being chastised when it is used. “A sunshade to go over the boom,”

“No Barbara”

“Duffle bags”

“I’m going to the loo” He escaped phone in hand for a few peaceful games of Solitaire and Sudoku, while I went on scheming. Sailbags, shoulder bags, Hydrovane wind steering gear cover, I’m not going to waste it. I’m not.

We were beginning to feel really fit. Rob’s black eye nearly gone and my head healing nicely. So now it was time for the big cook.

The juicy ginger I peeled, chopped fine, mixed with a little water and lots of brown sugar and simmered until it was nearly dry. The garlic we sliced and fried gently till brown. Then all the remaining veg, aubergines, onions, potato, soaked lentils and chick peas were cooked together with satay sauce mixes and the addition of a little extra peanut butter.

For the first time I used one of the round, handle-less stainless steel pans from my thermal cooker collection to make a Spanish tortilla with the last eight eggs, potato, dried herbs and cheese and baked in the oven. When Customs Officer Mike sniffed it and said “So you’ll eat all that today won’t you?” My positive answer to him was only a little white lie. Four eggs each we’d be harbour bound!

We both lost some weight, great exercise without even trying, in the constant motion and need to brace oneself. The only relief from this was to lie down in the berth and relax totally, just letting Zoonie rock one to sleep.

My black leggings were covered in white areas of salt that looked as if I’d been playing snowballs.

One of the million horizon scans revealed another sailing boat. So we radioed them up to see how they were doing.

The 15 metre, dark hulled Mirabella had a family of four on board and were heading for Opua to clear in. This was their first voyage across these waters and they had been dreading it because of all the terrible stories they had been told. They were excited to have had a “fantastic” sail down and even more so when we told them they had whales blowing infront of and behind them. False killer whales were all around us in small pods as we neared the end of our journey.

The on board music changed from Muse to fit the boisterous conditions to Clannad to mirror the silky surface of the sea reflecting the opaline clouds above.

On the afternoon of what we knew would be our last day at sea, we sat on the foredeck looking back down our lovely home to the way we had come. I leaned over the side of Zoonie’s bows to see if the logo had survived the lashings of the sea and was pleased to see they are both intact.

Slanting rays of pure sunlight illuminated the top few metres of the water to reveal an inner life of jellyfish and tiny pieces of shining silver like scraps of baco foil which must have been fish. Bigger predators were not far away.

Around Bream Head we entered Bream Bay at the mouth of the river leading up to Whangarei.

We could easily have come in at night but as there was a reluctance to end this amazing trip we slowed Zoonie down a little and arrived in Marsden Cove Marina with 1142 miles under our belts at 8.12am on Monday 22nd October after 8 days 23 hours and 18 minutes at sea. (35:50.20S 174:28.11E.)