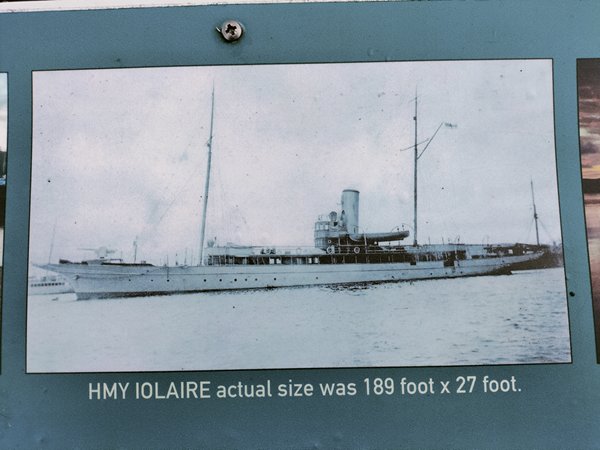

Approaching Stornoway on a fine, calm day aboard Zoonie, the natural harbour opened its arms in what would normally seem to be a welcome to the seafarer, but over to the right is a tiny buoy and a concrete pillar in the water, which open the door on an event that was the opposite to a welcome, in fact an appalling and cruel tragedy, still recalled with pain by descendants of the families. The loss of life aboard HMY Iolaire (eagle), when she hit the ‘Beasts of Holm’ rocks, robbed the Isle of Lewis of nearly all of its younger generation of men returning from the First World War on leave, in time to celebrate the New Year of 1919.

The post and buoy mark the site of the Iolaire wreck

The ill-fated vessel left the Kyle of Lochalsh in the evening of December 31 1918, loaded with tired but jubilant men mostly from the Royal Naval Reserve, their families keenly awaiting their return. Within a mile of her destination, for reasons that are not clear, she foundered.

As often happens, one hero, John F MacLeod managed to swim ashore with a light heaving line and enabled many of the 82 survivors to reach shore, but 205 men including 181 native islanders drowned, some weighed down by their heavy boots, and others who had never learned to swim.

A fishing vessel in the area at the time noted she was not on course for the harbour and the weather was deteriorating with poor visibility, and she had none of the modern aids to navigation we have these days which save lives at sea every day.

Benevolently the tragedy has been taken into the comforting arms of folklore and artworks, songs and poems have assisted in the process of grieving, and it has been included in the Arts and Humanities Research Council “Living Legacies (1914-1918)” Project, highlighting the extent of this loss felt by families and communities.

In 2019, to mark the primary centenary, First Minister for Scotland at the time, Nicola Sturgeon, and the then Prince Charles attended a memorial service at the location metres from the wreck. The Prince unveiled a new memorial in the form of the coil of rope, the light heaving line on top and the stronger, load bearing rope beneath, used by John F. MacLeod to save 40 lives.

Gone but never forgotten

So near her destination

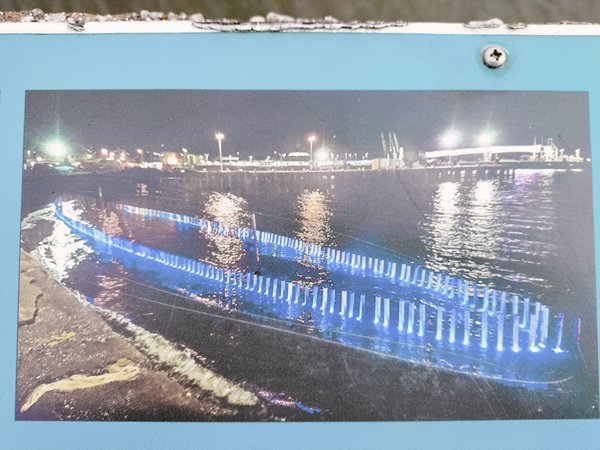

On the beach outside the harbour 281 wooden piles have been set into the beach to represent the total number of men on the ship and at high tide it is poignant to see the fine green weed flowing in the water like human hair.

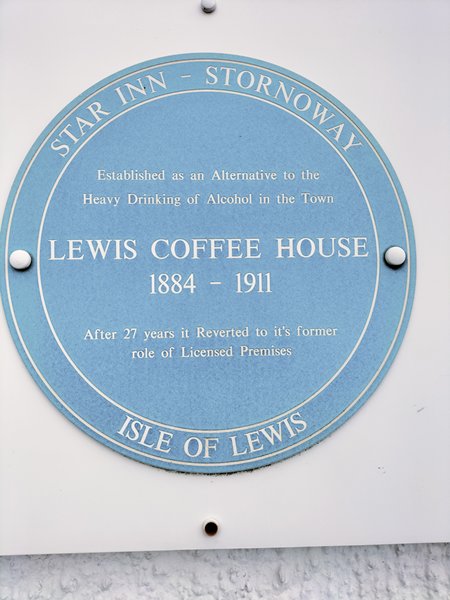

We motored into the inner harbour to find a surprisingly green and wooded scene with Lews Castle on the left and the modern marina on the right. Zoonie soon nestled in behind the lifeboat and numerous other characterful vessels and our first shore visit, via the Tourist office, was to the oldest pub in town, dating from the 1700’s, The Star.

Taken from The Gallows, a hill in the castle grounds with a sinister past

Closed for years, only partly because of Covid, it has recently re-opened and is attracting locals and hopefully mariners as well. Visitors in cars and Cruise-liner passengers soon pass through the town to other destinations, (along roads of some fine houses built for Lord Leverhulme’s managers) but with a few of the town pubs now closed permanently, maybe the remainder stand a chance.

A property reflecting the lifestyle of Lord Leverhulme’s management

Watching Glastonbury

American rock band ‘Blondie’ singer Debbie Harry and guitarist Chris Stein; strutting their stuff since 1974

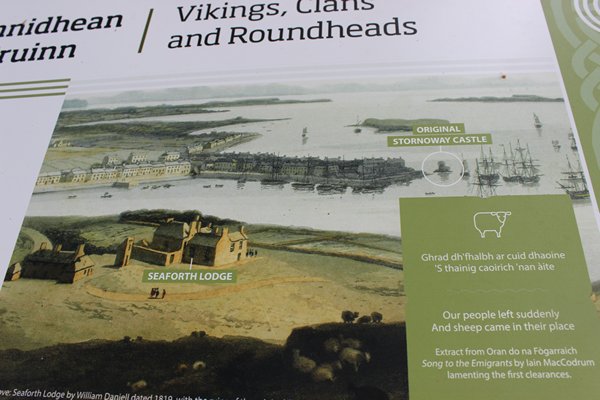

After the Norsemen left the islands in 1266 the King of Scots granted Lewis to the MacLeods in 1343. As we know they ruled for centuries, building the first Stornoway Castle on a small area of raised ground to the right as one enters the harbour. Apparently one can still see a tiny part of the castle incorporated into the present wall but I think one would need a more acute knowledge than mine to spot it.

The island above the old castle is now joined to the land on the right and is home to the locals’ marina. Visitors moor in the marina located above and left of Seaford Lodge, home of the Mackenzies

As I mentioned in part 2 of our Odyssey, Roderick MacLeod X caused such momentous problems for the clan, King James VI of Scotland gave Lewis to the Mackenzies of Kintail, otherwise called the Earls of Seaforth, in 1610. They weren’t much better as far as military aggression was concerned and succumbed briefly to Oliver Cromwell’s troops from 1653/4 when the castle was destroyed.

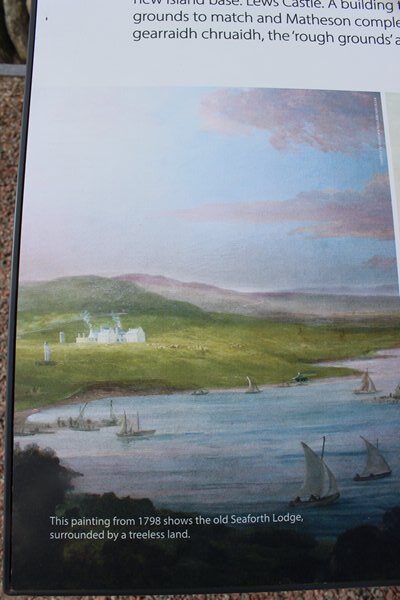

So, the Mackenzies needed a new home and soon set about building the substantial Seaforth Lodge pictures of which fortunately survive. You can see how devoid of trees the area was then, after the area had previously been cleared for farming by the indigenous people. Well, that would change under new ownership. The Mackenzie’s smelled the destructive aroma of profit and started clearing their land of people this time, in favour of sheep, sending the first farmers away to the New World so the clan chiefs could expand their profiteering plans.

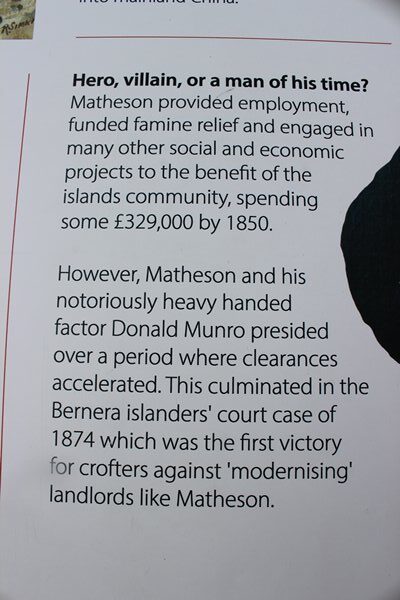

In 1844 wealthy businessman Sir James Matheson of Jardine and Matheson & Co, bought the island of Lewis for more than £190,000 (nearly £31 million in today’s money, if the quoted sum was from 1844, I wonder who or what institution, the money was paid to? The Lord of the Isles, Scottish Government?)

Sir James Matheson

The fortune came from money he made following the first Opium War with China 1839-42 which enabled him to expand his business empire into mainland China. That side of his life is well documented in case you are interested, and Alexander Matheson was James’ nephew and also in the family business. Alexander built Dunvaig Castle in Plockton on the mainland, to which we walked through pretty, lochside woodland when we were moored there.

His uncle, Sir James, wasted no time in re-shaping the estate he enclosed around his castle on Lewis, importing thousands of tons of top soil from the mainland to cover the peat mass and support tree-planting. Today the trees are mighty and the reshaped crevices and valleys, paths, drives and embankments make the area stand out from the surroundings. But what of the human cost both at home and abroad of his exploits, and how these historic actions shape China’s contemporary view of the west today?

The present-day grounds are delightful and during WWII, when the castle was requisitioned as a naval base and six Supermarine Walrus Seaplanes operated from the slipway, today children make memories by having fun learning water-sports.

Baron Leverhulme owned Lewis from 1918 to 1923 and by March 1919 recently returned war veterans started to take over his farms, which had been promised to them by the Scottish Government as places to settle post war. Imagine this was just two months after the Iolaire disaster. Amidst the shock and grief, feelings of belonging and a fresh post-war start to island life must have been running high. As I have mentioned the men of the Hebrides did not want to lose their independence and become the Lord’s employees, so finally, in 1923, William Lever handed over Stornoway town to the town council who set up a Trust that has run local matters since. Much of his land outside the town remained unsold and the inquiring parties proved to be more interested in shooting and fishing than running the land according to his plans.

The castle interior has been restored to the grand style of Lord Lever’s time and now has the UHI Outer Hebrides college of further and higher education attached. The University of the Highlands and Islands campus provides many courses including Energy Engineering, Merchant Navy and Maritime Training through to music and has alternative campuses on Benbecula and Barra; another good reason to stay on the islands or return to them later in life.

The castle provides a great place to stay if you can afford it, and a groom-to-be and his best man were preparing the ballroom for his imminent wedding reception

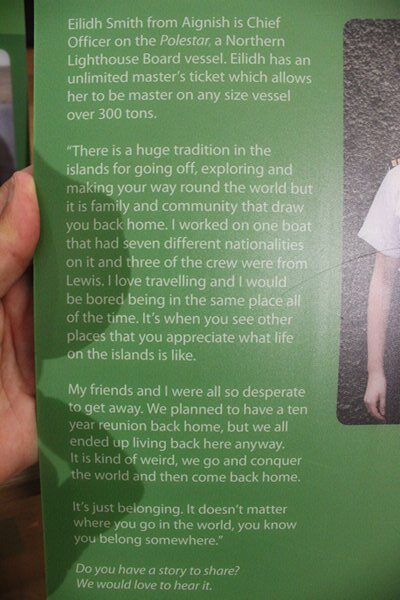

I have mentioned the advent of the hard fought for new Crofting Laws which have helped to keep the population on the island, and it was good to see that young people are making their futures in their birthplace, just as we found in Fiji, when we were visiting Fulunga. Island loyalty and a place to belong.

I have skimmed through the essence of the Outer Hebrides in these few blogs, there is so much more to understand beneath the surface; from the violent and heated birth of the rock base to the mosaic of human history, the weft and warp of human thought, the Harris Tweed fine woven cloth, that is the Outer Hebrides. A visit is highly recommended!