Whisky Galore – soon

Low grey clouds beckoned us forward and south on our last morning across Lewisian terrain that we were now familiar with, but including some fine lochs, set deep into the landmass, some smaller ones called Lochans, and also some tiny ones, Lochlets? Respect for ancestry and history was evident with modern cemeteries enclosing and enfolding ancient standing stones. We slid down beside glaciated Seaforth Fjord reaching seven miles inland and opening onto the Minch, leaving it behind us; and ahead of us lay Harris’ vast mountain range. The ease with which our little red car shoots up Mt Clisham hides the fact it is the highest mountain in Harris at 799 metres. It was foggy up there at the summit of Ardhasaig and yellow snow poles alongside the road showed how bleak and inhospitable it would once again be in just a few months’ time.

Our hopes for a little liquid hospitality and a gin tour at the newly formed (2015) Harris Distillery were dashed for a couple of reasons; despite the brochure saying tours were available six days a week, four other couples were as disappointed as us. Secondly, although we could buy their gin in the shop, their first batch of Hearach (Isle of Harris dweller) Whisky is still sitting, maturing in bourbon barrels and sherry butts, to be released to a thirsty world on September 23rd this year. The first reason was unacceptable, the second, understandable.

Eight of the nine botanicals used, and the kelp, help create their maritime gin

Their creation ethos and vision described in their own words; ‘was driven by a deep, abiding love for this place and its people. We have created a ‘Social Distillery’, with the future of Harris at its heart, an enterprise that will thrive for generations to come.’

I like the way they describe their whisky as ‘the first legal whisky to be made here in Harris’. Hide all those secret stills mamas!

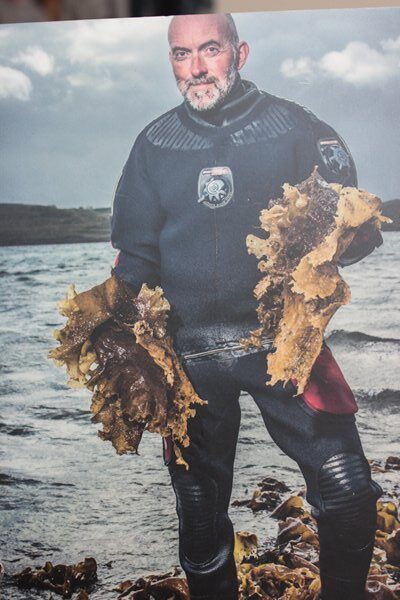

Lewis Mackenzie loves harvesting sugar kelp for the distillery

Maybe that’s where the lorry load of seaweed we passed as we were leaving the Calanais stone circle was heading.

The harsh rocky landscape we passed here reminded me of south west Ireland. Smoothed by glaciers and barely hidden by the thin grassy soil it takes a certain mindset to live here, and plenty of people do. The closeness to the shores of the Minch, provide easy fishing during clement weather, and the few sheep keep the ground neat. Run-rig ridges, sleeping since clearance times, might provide somewhere to grow crops but if the climate is now cooler and wetter, maybe not.

The remains of the run-rig ancient agriculture system

The road as you can see is narrow and windy; where a little elevation was needed in the construction, rocks have been taken from around with minimal disturbance to the surroundings in an area clearly loved and respected by the inhabitants now, and in times past.

Sympathetic road building next to a freshwater locklet(?)

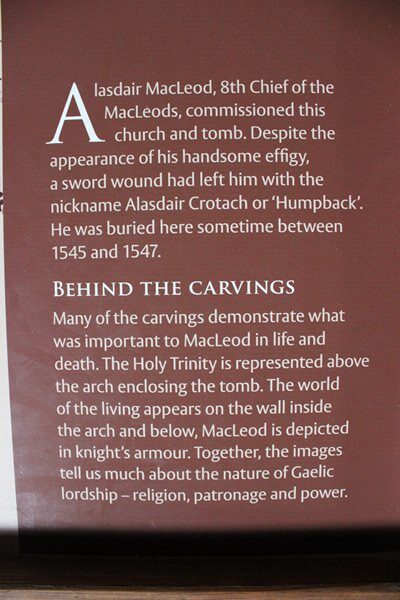

Clan MacLeod’s Church of St Clement

Looking out towards The Minch from the elevated cemetery of this beautiful and historically significant clan church, it wasn’t difficult to imagine the single square-sail birlinns of varying sizes sailing these waters between Skye, Iona and the Hebrides hundreds of years ago, even as far as Spain and Portugal, with Ireland’s coasts on route. If there was no wind, and depending on the size of the vessel, between 12 and 40 oarsmen produced the forward motion.

Alasdair’s arched tomb survived the Restoration of 1560 and two hundred years of dereliction

Birlinns like the one on the right depicted at clan burial sites were symbols of chieftain power

In just a few days we were to cover the same watery area, as Zoonie made passage under her single blue cruising chute inside the off-lying Shiants to Loch Scresort on Rhum.

Before Alasdair MacLeod, 8th Chief of the clan MacLeod’s men from Dunvegan Castle on Skye (we visited on one of our perambulations by bus, if you remember) arrived by sea and built the church in around 1520, some of their chiefs were buried in the Abbey cemetery on Iona.

Grave slabs showing typical Celtic symbols plus those ‘Knights Templar’ references to skulls and cross bones

The church was in regular use for a mere 40 years when the Protestant Reformation of 1560 caused it to fall into ruin for two hundred years. Then Captain Alexander MacLeod rebuilt it only for it to be severely damaged by fire three years later.

This sacred edifice, the very walls of which have been scarcely spared through the fury attendant upon religious change, which in its universal pillage devastated everything, and levelling the adjoining convent of friars and nuns to the ground, consecrate to the piety of his ancestors in former times, to God and St Clement, after been for now over two hundred years roofless and neglected, was repaired and adorned….by Alexander MacLeod of Harris in 1787 AD.

The Latin inscription on the marble plaque to recognise the work of Alexander MacLeod. I didn’t translate, but I did get the date right!

What we see today is a result of the repairs instigated by the Countess of Dunmore in 1873.

During the age of Scottish bards from the 15th to the 18th centuries and while the church was in decline, Mary MacLeod, Màiri Nighean Alasdair Ruaidh, was a leading figure in a group of female poets two hundred years before Robbie Burns was born. She wrote fine poetry insisting on the importance of music and capturing themes of strength, wisdom and generosity. She lived much of her long life in Dunvegan Castle, acting as nurse to many generations of MacLeods, and when she died, and in the clan MacLeod tradition, she was brought across the water for burial, it is thought, within the church walls near the grave slabs. She asked to be buried face down so she could not tell any more lies! (lies meaning stories in the bardic sense, I wonder? I detect a sense of humour there.) Her dates are surprisingly vague; she was born sometime between 1569 and 1615, and died between 1674 and 1709!

Is Mary there I wonder, beneath the polished stones, face down?

Had she been born a few decades later I can picture her sitting before a roaring log fire in one of the tapestry clad, stony rooms of the castle on Skye, chatting with Flora MacDonald about their interesting experiences and opinions. Bonny Prince Charlie’s escape to Benbecula and bard Mary’s latest morality poem for the local children.

The locals in the village of Rodel, where St Clements rests, always knew when Mary was coming their way as her silver topped staff tapped on the cobbles outside their homes. How amazing to live in the company of such compassionate and talented people, let alone be nursed through childhood by one.

Seanchaidhs, (bards) or oral historians were at the heart of pre-literate Gaelic culture, composing and safeguarding stories, songs, poems and traditions until the advent of reading and writing and printing preserved these priceless gifts from the past, forever.

The connections between images on the gravestones at St Clements and those we saw three days before at St Columba’s church near Stornoway and the Abbey on Iona, really help one to visualise this area not as separate islands, with distinct cultures, but as a Scottish offshore nation, not separated by water but linked by maritime routes, locally and to other west European countries.

So, what about the name; St Clements? Perhaps the church is named after St Clement, patron saint of mariners and marble workers, (there is metamorphosed marble on Iona and the Hebrides) or maybe the church offered a clement location of mercy, a respite from the seas, a place of peace and rest. Who knows for sure. Mysteries fire the imagination and feed the appetite of enquiry.

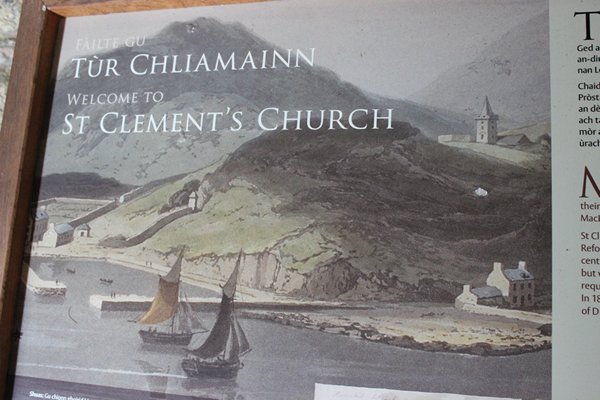

A painting of the church from 1814, notice the later rig style of the vessels

The Rescue of Roineabhal Mountain

A short walk from the church is Mount Roineabhal, reaching 460 metres upwards with a top of anorthosite, a rock similar to the moon, and by an immense amount of human effort over a period of 13 years from 1991 to 2004, it was saved from becoming ‘the gravel pit of Europe’, using the eqivalent of six atom bomb explosions during its predicted life, to extract one million tons per year of gravel, and pave the roads of Europe and beyond. Central to the effort was Alastair McIntosh, whom we met when he gave a short talk in the community centre on Iona.

I apologise for this drab photo of the mountain. I would love to spend a few days, in fine weather, doing it photographic justice

The people of the area were swayed at first by the promise of jobs and finance coming into the area; in 1993 62% voted for the quarry during a turn out of 61%. Two years later, when they realised what they would be losing thanks to Alastair reuniting them with their spiritual and cultural historical connections, in a turn out of 83%, 68% of the votes went against the quarry plans.

It was another eleven years of struggle before Lefarge/Redland, in a meeting in the Harris Hotel announced they were withdrawing from the project. The whole story is a long and fascinating one, a journey if you like with Alastair as the guide, and forms a large part of Alastair McIntosh’s great book ‘Soil and Soul’. The other major part of this work is the battle to put the tiny island of Eigg into the hands of the resident community and out of the hands of a defective landlord. The start of many similar projects.

Four years younger than me and a man whose passion for humanity and the world we live in is obvious in the way he speaks and writes; he lectures worldwide on new economics, community and non-violent strategies, in particular to top brass at military academies. He writes beautifully and I have just started his book, ‘Poacher’s Pilgrimage’, about his solitary walk from the mountain I have just mentioned, right up through Harris and Lewis to the Butt at the top, where we explored the lighthouse. Naturally I recommend him and his books.

We spent a few minutes at Leverburgh Ferry Port, through which the mined gravel would have been exported, and looked out to the Caolas na Hearadh, the rock-strewn stretch of water that separates Harris from North Uist, the waterway to the Atlantic, before moving on to the wonderful wide sandy estuary at Scarista; one of the most isolated, wild and magnificent places I have ever seen; inspiring a well-recorded cornucopia of beliefs, ideas and imaginings in Hebridean minds.

Looking westwards towards the Atlantic

Roineabhal brooding, but intact, in the background of the two pictures above

What a great four days. But that is not all. I have yet to tell you about Stornoway itself, Lews Castle and the eternally tragic Iolaire disaster of 1919.