Part 1/4

A Short Odyssey in the Outer Hebrides

Part 1/4

Northwards up the Isle of Lewis to Port Ness

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to live in a different era and an entirely alien location to the one you are used to? That’s what I love about travelling and exploring new places. One moves around through history and locations and then returns to the present to prepare for the next instalment. There is plenty to feed the imagination and transport one back through time on the Outer Hebrides.

On route to the most northerly point of the Outer Hebrides, the Butt of Lewis, we stumbled across the Steinacleit Stone Sets, a corrupted stone circle or burial cairn, discovered by crofters digging peat back in 1920. Its age is unknown; some hazard they are around 2000 years old or possibly Neolithic, going back as far as 10,000BC. Either way the area would have been a spectacular place to live; warmer than now and easy to grow a diversity of crops including oats, barley and potatoes, to support small communities. Trade routes by sea meant the population was not cut off from the rest of Europe; indeed, the first inhabitants arrived by sea, what an adventure that would have been. Rob and I felt a sense of achievement when we arrived in Zoonie, knowing how tricky the Minch can be in bad weather. What must it have been like to be arriving at an unknown island?

In the photo looking over the circle towards the lake you can see an island in the middle. It is thought that this was the site of a homestead 2000 years ago, the water offering protection from hostile visitors, while up the hill behind us were the remains of a stock enclosure. Places like this always remind me of Stonehenge where only the oldest and hardest evidence survives above ground.

Onwards to David Stevenson’s red brick lighthouse built in 1862. I haven’t come across many brick lighthouses, have you? The rock of the Outer Hebrides is Lewisian Gneiss (some outcrops are over 3 billion years old, only 1.5 billion years younger than the earth itself!) and it is too hard for quarrying and building, hence the use of brick.

There was a two hour walk around the Butt shown in red on our map and as the day was dry, we set off, heading west. The coast line was as rugged as you might expect and some of the gneiss had been twisted and squashed to such an extent it was named plasticine rock. Sea birds including kittiwake and gannets proliferated and the onshore wind sent plumes of spray off the crashing waves; I was relieved it was an onshore wind. One of the stacks is known as The Pygmy Isle because the tiny bones discovered by early, death defying explorers were thought to come from pygmies. They are of course the bones of seabirds and small mammals the birds have eaten.

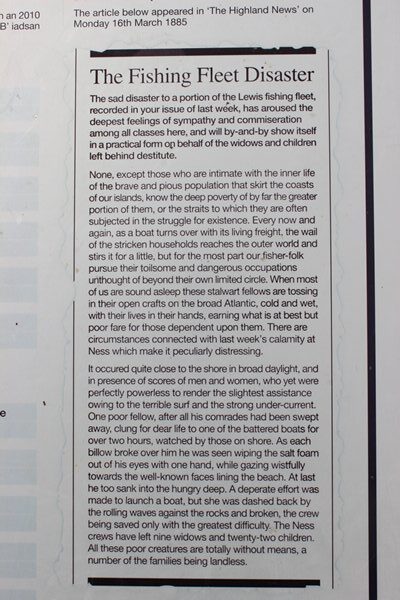

We came to look down on beautiful Chunndail Beach, bathed by the Atlantic and loved by surfers, and read of the terrible disaster that befell two returning fishing boats during a daylight gale on the 5th March 1885. Just imagine what it was like to be a mother or father, sister or brother watching from the cliffs above as your beloved fisherman perished in the mountainous surf beneath and you could do nothing to help them. It sent a chill down my spine just being there reading the story. To think of the struggle these people had at times to gather enough food to feed their families and to know that an incident like this meant to the nine women and twenty-two children who were left vulnerable with no male family member to provide for them, unlike us with our easy, supermarket lives and welfare state. You can see why community was so important then.

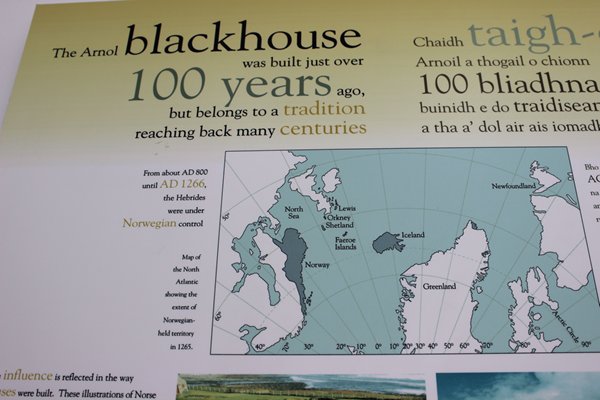

The flowers by the burn running through Eoropie

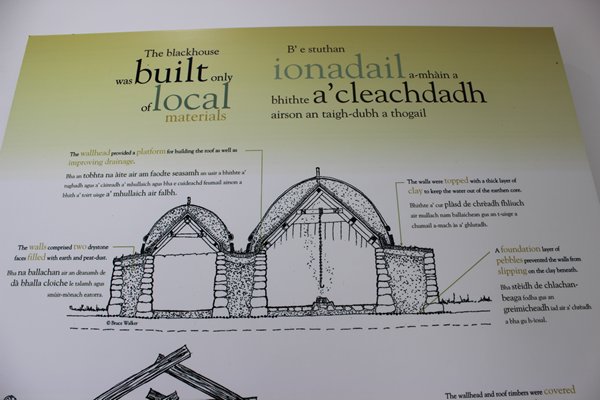

All the lost men were from Eoropie, a little village we walked through on our way back to the car. There were numerous ruins of blackhouses, often in the gardens of modern occupied dwellings, and once back on the road we drove to Arnol, the locations of an ancient township dating back to at least 2000 years ago. The intact blackhouses were built around one hundred and fifty years ago and all copy the Scandinavian design. They lasted hundreds of years, with a new roof of oat straw each year to replace the smoke infused fibre that was then spread on the rig and run lazy fields.

The gathered stone used to clear the fields also provided the double layer walls, with earth and peat dust infill to prevent damp. Long stones were incorporated up the wall (as demonstrated by Rob) so access to the level joining the inner and outer wall could be reached. Then the wooden roof could be built and the thatch replaced easily. Wood was scarce as the trees were felled eons before. Often driftwood was gathered from the beaches and would be taken with a family if they moved away, which is one reason so many of the ruins are roofless. Another reason is the roofs were set on fire to get the families out during the brutal clearances.

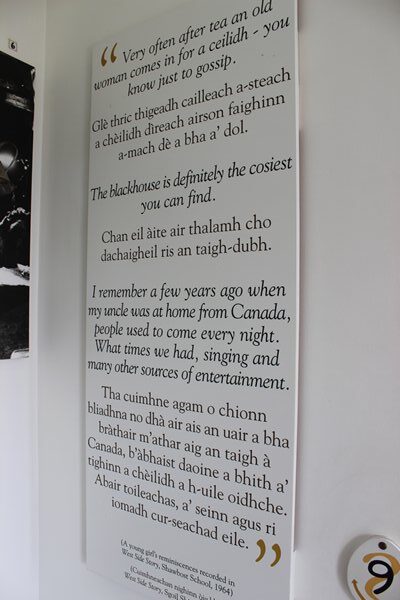

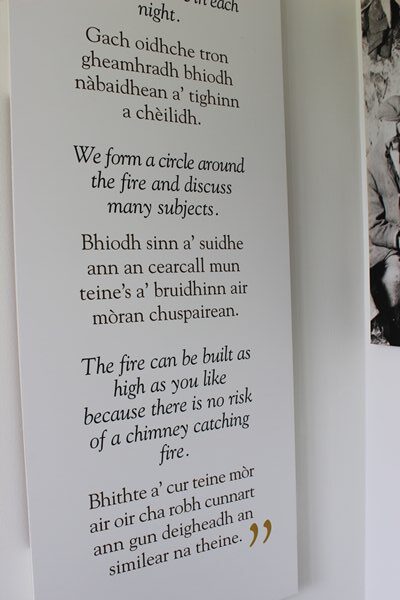

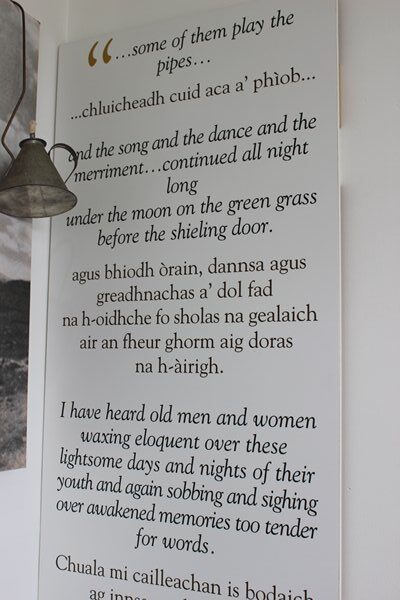

People were still living in these remarkable homes up to the 1970’s. Two characteristics of them that were novel were, the animals lived under the same roof, for warmth, protection and because then only one building had to be built, and secondly they historically had no chimney. Not sure I would have thrived in that smoky atmosphere, certainly life expectancy would have been shorter then. But they enjoyed the quality of community life in their ceilidhs, and sharing their daily tasks like farming, fishing and weaving etc. It would have been easy to enjoy the satisfaction of such activities after a day of physical work.

One way of life that has transcended the changes in house styles from blackhouses, through stone crofters’ cottages to modern pebbledash homes is the use of peat as a fuel.

As I mentioned the trees that once covered these islands were felled by the first human inhabitants, so without the thirsty tree roots to soak it up the plant-life became water-logged, died and rotted down to form peat. Cut into bricks and stacked, these days on wooden pallets, to dry firstly in the fields so they are lighter to transport; then in piles outside most houses ready for use all year round.

The only trees we saw that day grew in moist ravines, and pretty cotton grass shimmered in the generous breeze like a falling snow shower over vast expanses of peat moorland. We could see for miles.